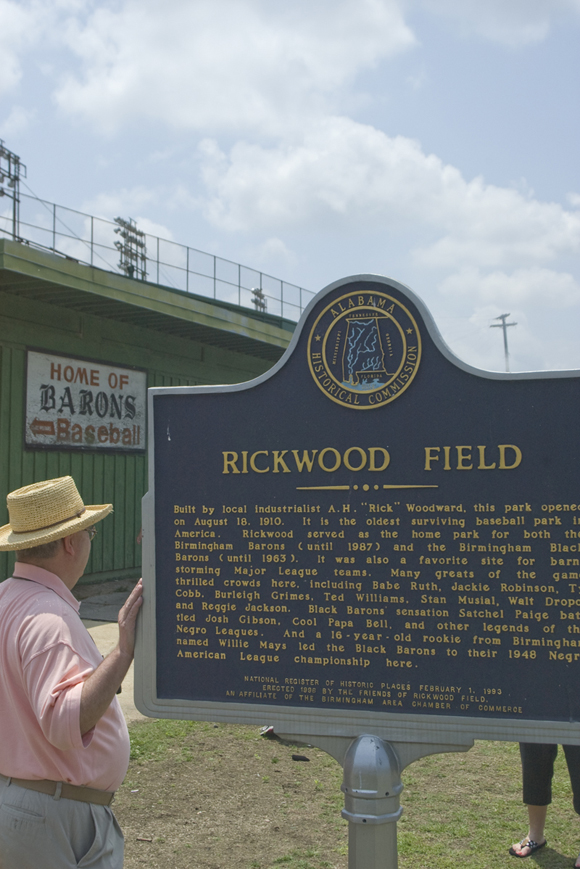

Carrying the weight of 100 years of baseball history — never mind the 100 years of social and civil-rights history as well — is an awfully heavy load for any ballpark. But Birmingham’s Rickwood Field was equal to the task during the 15th annual Rickwood Classic Wednesday, as fans celebrated the upcoming 100th anniversary of this historic venue. Some thoughts on that impressive legacy and where we are today.

FAST FACTS

Year Opened: August 18, 1910

Past Tenants: Birmingham Barons (Southern League), Birmingham Black Barons (Negro Leagues)

Address/Directions: 1137 2nd Av. W., Birmingham, AL. From I-20/I-59, take Hwy. 78 south at Exit 123 to Hwy. 11, also marked as 3rd Avenue West. Go west (right) on 3rd Avenue to 12th Street West. Hang a left (the turn is marked); the ballpark will be two blocks south on your left.

Certainly at the core of the event was a baseball game: a Class AA Southern League matchup between the Tennessee Smokies and the hometown Birmingham Barons. But with anything old in the South, the actual meaning of the event reverberated far beyond the action between the foul lines. In many ways, the most important lessons of the day extended far outside the foul lines.

For better or worse, much racial history can be seen through events at Rickwood Field. The ballpark was a hub of baseball activity since opening in August 1910, hosting various professional minor-league teams as well as the Birmingham Black Barons, one of the preeminent Negro Leagues franchises. (Among the legends who played for the Black Barons: Satchel Paige and Willie Mays.) Racial integration didn’t necessarily come easy to Rickwood Field – side events hosted there included KKK rallies, some as late as 1946 — but it did. By the 1950s MLB teams played integrated exhibitions at Rickwood Field, despite an edict from Bull Connor that integrated baseball was forbidden in the city (and no one seemed to care), and further integration in professional baseball saw the demise of the Black Barons in 1963. By the 1960s a talented group of African-American players, including future Oakland Athletics Vida Blue and Reggie Jackson were making their marks on the field with the Birmingham A’s. It took years of opposition to segregated baseball to reach a time when integrated baseball was an accepted practice in a city where many infamous civil-rights battles were fought.

Now, this isn’t to say that Rickwood Field today is this racially diverse nirvana where skin color doesn’t matter. Indeed, one of the failures of Minor League Baseball has been to connect with minority populations across the county: Black, Hispanic, Asian alike. Before the start of the season MiLB President Pat O’Conner challenged affiliated teams to change this state of affairs, we’re told.

Now, this isn’t to say that Rickwood Field today is this racially diverse nirvana where skin color doesn’t matter. Indeed, one of the failures of Minor League Baseball has been to connect with minority populations across the county: Black, Hispanic, Asian alike. Before the start of the season MiLB President Pat O’Conner challenged affiliated teams to change this state of affairs, we’re told.

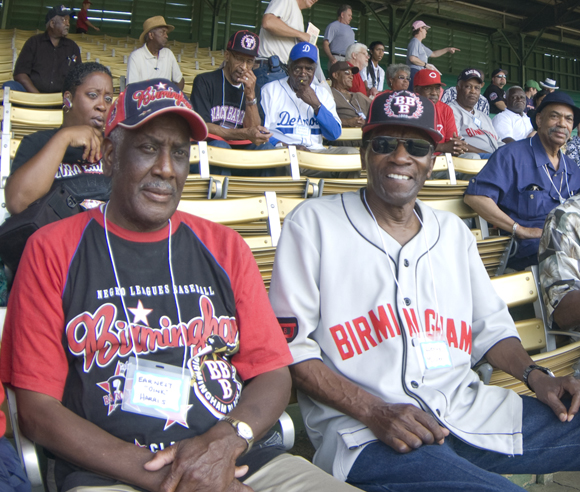

But if yesterday’s Rickwood Classic is any indication, baseball still has a long ways to go. It was a predominantly white crowd in a city with a majority African-American population – and a sizeable majority at that, some 73+ percent, according to the 2000 U.S. Census. Take away the former Negro Leagues players honored there and the crowd would have been even whiter. It was also an older white crowd, heavy on the nostalgia. Now, there’s been a lot of recognition in recent years about the Negro Leagues and barnstormers like John Donaldson, but we’re not sure the definitive history of Negro League baseball has yet to be written. It was a much larger industry than thought, and the notion that there are only three existing ballparks once hosting Negro Leagues baseball is a load of hooey. We can name several off the cuff: Phil Welch Stadium in St. Joseph, Mo.; Jack Brown Stadium in Jamestown, N.D.; Cardines Field in Newport, R.I.; Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, N.J.; Engel Stadium in Chattanooga; Point Stadium in Johnstown, Penn.; Durkee Field in Jacksonville; Municipal Stadium in Hagerstown, Md.; McCormick Field in Asheville, N.C.; and, of course, Rickwood Field. We’re guessing there are lots more. And there are undoubtedly stories connected with all these facilities.

The sad thing is, by not reaching out effectively to the city’s African-American population for the Rickwood Classic, the Barons and MiLB were depriving that population of a truly wonderful experience. And we don’t mean to rag on either entity: the Barons go above and beyond by hosting the Classic annually: playing a single home game in a ballpark not their own is a logistical pain in the butt, and the fact that the game proceedings went so smoothly despite the lack of infrastructure to handle a crowd of 9,448 is a testament to the Barons. And we’ve already discussed O’Conner’s challenge to MiLB: it’s a strong start.

True, Rickwood Field is showing its age. The Friends of Rickwood have done a marvelous job in maintaining the old ballpark and restoring parts of it, turning it into a “working museum” of sorts. There’s still a lot of baseball played there: some local colleges and high schools play home games there. Still, it could probably use another round of renovations: fencing on the edge of the field is in rough shape thanks to vandalism, concrete is badly crumbling in some key spots, and the box seats could use a coat or three of paint.

This is not to say you shouldn’t avoid any game at Rickwood. Attending a Classic, however, is the best way to appreciate baseball’s past and present.

THE BALLPARK

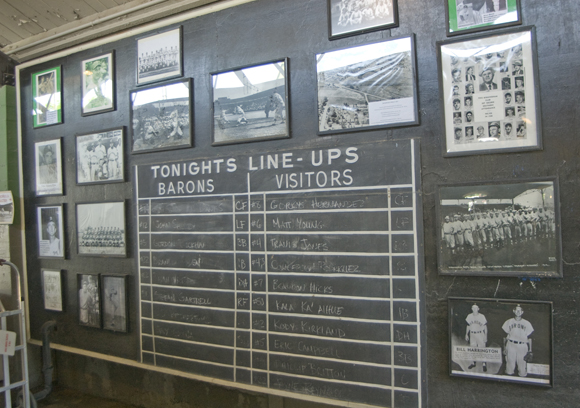

The ballpark design is classic: a covered U-shaped grandstand running a full block along the first-base line and a half-block down the third-base line, with a short home-run porch in right field, which gives way quickly to two levels of billboards – some historic, some real. A hand-operated scoreboard, topped with a nonfunctioning clock, dominates left field.

Most of the fans opted to sit in the general-admission seats under the grandstand roof; on a hot day with precious little breeze moving through the ballpark, this was the smart move. The theater-style seats in the sun were only partially used.

For those who aren’t old-ballpark freaks (like the operators of this website obviously are), a tour of Rickwood Field is instructive in how public facilities functioned a century ago. When it was built, Rickwood Field was opulent but not trend-setting in terms of design. It was, however, the first steel-and-concrete ballpark built in the minors, something that had happened only on the Major League level four times before, and there sometimes only partly. (When Fenway Park opened two years later it sported a steel and concrete frame but still featured wooden stands, which later burned down.) Like many other old ballparks in the minors and the majors, there was a small building at the front of the facility – the front office, which is where the phrase comes from – housing team offices and ticket functions. That building is detached from the grandstand of the ballpark, with concessions, restrooms and clubhouses tucked under the grandstand. It’s a baseball ballpark design that was already established when Rickwood Field was built and lasted well into the 1950s; you can see echoes of that design in ballparks like Clinton’s Alliant Energy Field.

This design put the emphasis on getting fannies into the seats: concession sales were a nice benefit but not the focus of the design. Once in their seats, fans were expected to spend most of the game there. Crowds were predominantly male, and chances were pretty good that at any given time you’d find some action in the form of betting. Today you still find pockets of betting at ballgames — just spend some time in the Wrigley Field bleachers — but for the most part the modern ballpark is an entertainment venue competing with the movie theater in terms of offering amenities to fans.

The Friends of Rickwood have done a marvelous job in preserving and maintaining the ballpark, but there was one force much more powerful that kept the ballpark as it was in the past: inertia. Rickwood Field doesn’t sit on desirable real estate; it was cheap land when Rick Woodward built the place, and it’s cheap land now. No developer has ever come along and made a play for the Rickwood Field site. In many cases inertia is the most powerful force when it comes to historic preservation, and that’s certainly been the case with Rickwood Field.

THE GAME

Lest we forget there was a game played as part of the Classic, and a pretty good one: an extra-innings affair that saw the hometown Barons lose to the Smokies, 8-7, in 12 innings. The Smokies were playing as the Appalachians; too bad the Montgomery Biscuits couldn’t have been scheduled to play in the Classic, as the first game at Rickwood featured the Montgomery Climbers as an opponent.

HISTORY

Rickwood Field opened on August 18, 1910, as the home of the original Birmingham Barons Team owner Rick Woodward wanted an opulent home for his team and budgeted $25,000 for the project; Connie Mack helps him choose a site, lay out the diamond and specify a layout similar to that of Shibe Field, down to the field measurements. Opponents of public funding of ballparks will be happy to know that little has changed in the last 100 years: the final financial tally for the 7,00-seat ballpark was $75,000. In those days, that was real money.) A contest in the local newspaper yielded the name of Rickwood Field, a mashing of the owner’s name.

Changes were made to Rickwood Field in the 1920s, however, that yielded the ballpark we see today: the roof was extended to new seating in the right-field corner, while the Spanish Mission style front office was added in 1928.

The final pro days at Rickwood Field saw the historic venue serve as home to the Southern League’s Birmingham Barons, who fled to the suburbs and Regions Park in 1987. The sad truth is that Regions Park saved baseball in Birmingham: fans had tuned out pro ball in the city, and the final year at Rickwood Field saw the Barons draw only 147,279. Certainly not the worst attendance seen at Rickwood Field — the Charlie Finley-owned Birmingham A’s drew 21,016 in 1973 — but not enough to keep pro baseball in the Birmingham city limits.

CONCLUSIONS

It’s hard to argue with the success of the Rickwood Classic: the announced crowd of 9,448 (in a case where that number bore some semblance to reality) is double what the Barons draw on an average night at Regions Park. It’s also hard to argue with the good intentions of the game’s organizers in terms of recognizing the importance of the Negro Leagues and African-American ballplayers.

But the Rickwood Classic also shows how far we have to go to exist as a truly racially integrated county and how much work baseball needs to do to make that happen at the ballpark. Minor League Baseball has the potential be a leader in this, but it takes more than an annual game at Rickwood Field. It takes some aggressive hiring in baseball front offices, some heightened marketing to youth, and generally a more aggressive attitude. Recognizing the challenge is a key step in this process; let’s hope the work continues.