Today’s MLB owners may be working largely behind the scenes—how many of you could pick Ray Davis or Bruce Sherman out of a lineup? —but when pro sports were in a more precarious financial position, celebrity owners raised the public profile for teams needing a boost at the box office.

Some early team owners were flamboyant figures, more like gregarious barkeeps than serious business owners. Chris von der Ahe, for example, led the outlaw American Association into existence after transforming Sportsman’s Park into a serious St. Louis venue, selling beer by the mug and whiskey shots for a quarter. Knowing little about baseball, he crafted what would become the modern baseball experience, acting as the public face of the team in a celebrity fashion. In 1885, he erected a large statue outside Sportsman’s Park – not in tribute of any star on the field, but of himself, the “Millionaire Sportsman.”

But the success of the St. Louis Brown Stockings (now Cardinals) would not last, and when he lost player-manager Charlie Comiskey (who, ironically, copied some of Von der Ahe’s strategies in building Comiskey Park and associated development), Von der Ahe’s baseball empire crumbled.

After von der Ahe, baseball owners decided to take a more measured approach to celebrity: yes, Col. Jacob Ruppert and John Brush and Harry Frazee did not avoid being in the headlines, but they did so as serious businessman, promising to take care of their stars and putting the best team possible on the field. Let the Broadway stars benefit from a press agent and a presence in the gossip columns; the MLB owners would remain on the side, with exposure limited to the sports pages and the business section. Not that there weren’t celebrities seeking an MLB team: Composer and performer George M. Cohan was repeatedly rebuffed in his efforts to buy a baseball team.

That changed once again when Bill Veeck hit the scene. Whether by dint of a larger-than-life personality or instincts that told him making the newspapers would be good for his team, Veeck certainly dominated the headlines during his ownership stints with the Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns and Chicago White Sox. A genius whose presence can still be felt both in Major League Baseball and Minor League Baseball, Veeck turned promotions on its ear, using his imagination to keep his teams in the news. Other high-profile owners who promoted themselves as much as their teams: the Athletics’ Charlie Finley and the Braves’ Ted Turner.

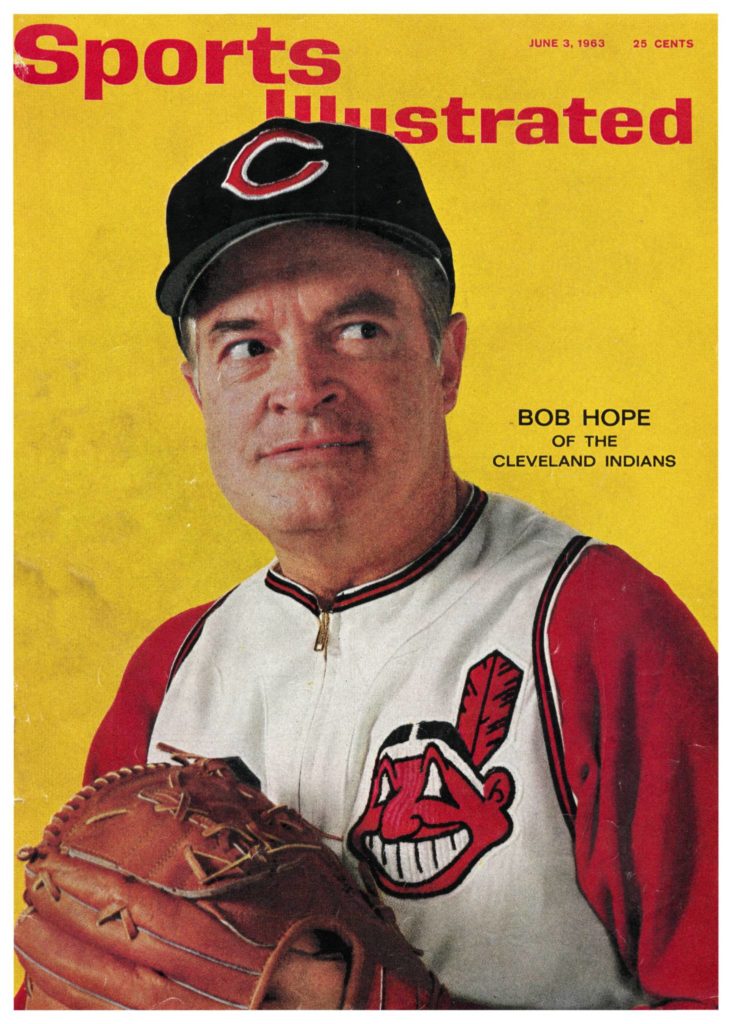

Veeck also did one thing that promoted his Cleveland Indians: he embraced the sale of a small chunk of the Indians to entertainer Bob Hope in 1946. A native of Cleveland, Hope grew up as a fan of the Indians and jumped at the chance to own a small share of his hometown team. He held onto that share even with the departure of Veeck, making promotional appearances for the team over the years. He even attempted to buy the Washington Senators in 1968 but was outbid by Minneapolis hotelier Bob Short.

Hope’s partner in crime: Bing Crosby, who invested in the Pittsburgh Pirates the same year Hope invested in the Indians. By this time Crosby and Hope were a solid show-business pair, performing together on Crosby’s radio show and on stage, and then making a series of popular Road movies, beginning with the Road to Singapore in 1940. At the time Crosby was one of the most popular entertainers in the United States thanks to a series of hit series and maximum exposure hosting The Kraft Music Hall on NBC. Live and radio appearances with Hope revealed an easy-going rapport between the two, and that professional relationship extended to professional baseball.

Crosby, an avid sports fan who also participated in the creation of the Hollywood Park Racetrack in Inglewood (now the site of a new Rams/Chargers NFL stadium under construction), was one of the few people to openly own shares in two MLB franchises, buying 5 percent of the Detroit Tigers in 1957. Commissioner Ford Frick allowed the dual investments, ruling that Crosby did not have a substantial interest in the Tigers—against the rules of the game at that time. Crosby held onto his 15 percent minority stake in the Pirates until his death in 1977.

At the time the Pirates and the Indians were two of the most solid teams in baseball, but the Crosby and Hope experiences didn’t lead to a flood of celebrities buying into Major League Baseball. Until 1961.

Gene Autry had made his wealth not only as a singing cowboy, but as a savvy businessman who invested early in radio and television ventures, including Los Angeles’ KTLA. He parlayed some of that wealth into the ownership of the Los Angeles Angels in 1961. Autry didn’t go out looking to buy an MLB team, with his first contact with baseball officials an inquiry about landing Angels radio rights for one of his stations. But with MLB rushing to expand thanks to the threat of the Continental League, Autry was recruited to invest in the Angels. Autry never saw his beloved Angels win a World Series—he passed away in 1998, and the Angels didn’t win a title until 2002.

One more celebrity owner to note: Actor and singer Danny Kaye was an original owner of the Seattle Mariners, who entered the American League in 1977. A Brooklyn native who grew up a Dodgers fan, Kaye was a lifelong devotee to the game.

Today, we still have high-profile celebrities and athletes investing in MLB franchises, but it doesn’t feel the same. Comedian and HBO host Bill Maher is a New York Mets minority investor, Earvin “Magic” Johnson is part of the Los Angeles Dodgers ownership, and Seattle Seahawks QB Russell Wilson (a former MiLB player) has been announced as potential Portland team investor. Bill Murray is famously part of the St. Paul Saints (independent; American Association) and Charleston RiverDogs (Low A; Sally League) ownership group, while boy-band alumnus Nick Lachey owns a minority share of the Tacoma Rainiers (Class AAA; Pacific Coast League).

This article first appeared in the Ballpark Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? It’s free, and you’ll see features like this before they appear on the Web. Go here to subscribe to the Ballpark Digest newsletter.