Beer has been closely associated with professional baseball since the game’s earliest days, but it was not initially a marriage welcomed by owners. In fact, the National League once expelled teams for selling beer at the ballpark. But over the years that relationship changed, and over time baseball became a prime marketing tool for breweries. Here are some notable examples.

In the game’s earliest days, beer was the enemy of the National League. In fact, the original American Association—the “Beer and Whiskey League,” as it was dubbed by National League potentates—began in 1882 after several teams were booted from the NL for selling beer and whiskey at the ballpark. NL owners sought a cleaner image for the professional game of baseball, and it was no secret that beer and whiskey attracted a coarser crowd to the ballpark, albeit one that spent enough money to keep teams afloat. Or, afloat for a while: the American Association ended up folding in 1891.

But the marriage with beer would end up being a prime financial boost for MLB teams, past the concessions revenue. As revenue from game broadcasts on radio and television rose, so did the financial commitment from breweries. After World War II, America saw consolidation among small breweries, first seeking to expand their regional presence and then their national buys. And what better way to reach a mass market of beer drinkers in the 1950s and 1960s than through sponsorship of baseball games?

Some brewery owners even went to the point of buying baseball teams. Col. Jacob Ruppert turned the New York Yankees from a cellar dweller to a championship juggernaut using the same corporate principles he laid down when running the Jacob Ruppert & Company brewery in New York City’s Yorkville neighborhood. August “Gussie” Busch Jr. turned a St. Louis regional brewery, Anheuser-Busch, into a national giant and along the way bought the St. Louis Cardinals in 1953, putting it on solid financial ground, first by buying Sportsman’s Park and then pushing city leaders to build a new ballpark. All three Cardinals ballparks have been called Busch Stadium, though Busch did push the limits when he tried to name Sportsman’s Park Budweiser Stadium. At that time MLB rules prohibited corporate naming rights, so Busch circumvented those rules by creating a new brand, Busch Bavarian Beer, to leverage the Busch name in 1955. He bought Sportsman’s Park from Bill Veeck and the St. Louis Browns, who were sold to National Brewing Company owner Jerold Hoffberger and moved to Baltimore. National Bohemian Beer (popularly known as “Natty Boh”) became a natural major sponsor for both the newly minted Baltimore Orioles and the nearby Washington Senators—the price for letting the team move into the Sens’ territory. And most recently, Labatt Brewing Company was the original owner of the Toronto Blue Jays, selling to current owner Rogers Communications in 2000.

But most breweries worked in conjunction with teams, not owning then. In those days, the relationship between beer and baseball was close. When WGN-TV began broadcasting Cubs and White Sox games in 1948, local sports personality Harry Creighton was on hand alongside Jack Brickhouse to promote beer advertisers—and even drinking their products on the air, something you’d never see today. (One reason why this would have been encouraged: in 1946, fully half the television sets sold in Chicago were sold to taverns. Many folks watching Creighton put one back probably would have been doing the same.) Sponsor placement were not subtle—A Ballantine Blast! A White Owl Wallop!—so folks who complain about the commercialization of baseball these days don’t remember that the same thing was going on 50 and 60 years ago.

What catapulted the beer and baseball marriage into prime time—literally—was the rise of television in the late 1940s and 1950s. Before TV, beer advertising was a child of radio, sponsoring broadcasts and scoreboard displays.

And when these regional brewers went national in the 1950s, baseball advertising was a prime line item in their marketing budgets. When the Minnesota Twins debuted in 1961, the Hamm’s Bear was a prime component in television commercials during game broadcasts, with the Hamm’s Beer jingle (“From the land of sky blue waters…”) promoting the local brew. That same year on TV saw Narragansett Beer sponsoring the Boston Red Sox, Carling Brewing sponsoring the Cleveland Indians, Stroh Brewery sponsoring the Detroit Tigers, Schlitz Beer sponsoring the Kansas City Athletics, Falstaff Brewing sponsoring the Los Angeles Angels and San Francisco Giants, Pittsburgh Brewing (Iron City Beer) sponsoring the Pittsburgh Pirates, and Hudepohl Brewing sponsoring the Cincinnati Reds (then billed as the Redlegs). (Ironically, the Los Angeles Dodgers didn’t have a beer sponsor in 1961.) Here are some beers closely associated with MLB teams:

Knickerbocker Beer and the New York Giants. As noted, Col. Ruppert made his fortune as a brewer, but he didn’t push any major marketing moves involving the Yankees and Knickerbocker Beer. Keeping the two businesses separate may not have been the best long-term play, and after his death in 1939, his heirs were eventually forced to sell the brewery and the Yankees at discount prices. Knickerbocker ended up owned by rival Rheingold Beer and became a major sponsor of the New York Giants, the Yankees’ great rival during the Ruppert era. The Polo Grounds scoreboard featured a Knickerbocker holding a beer and advising the crowd to “Have a Knick.” Broadcaster Russ Hodges would tell fans to “Have a Knick, feel refreshed” as part of a daily contest.

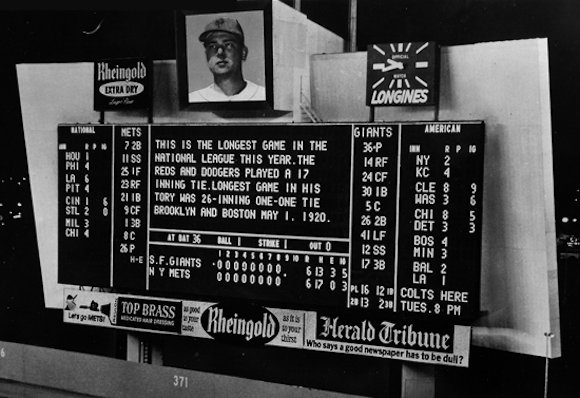

Rheingold Beer and the New York Mets. When the New York Mets set up shop temporarily at the Polo Grounds, Rheingold became the major scoreboard sponsor and stole a page from the Schaefer playbook: the h and the e in Rheingold lighting up to indicate hit or error. That relationship carried into Shea Stadium, where Rheingold sponsored the next-generation high-tech scoreboard.

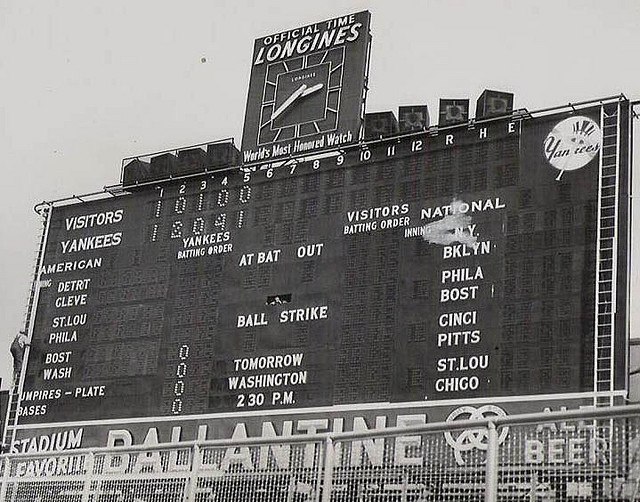

Ballantine Beer and the New York Yankees. After the Yankees were sold to Dan Topping and Del Webb in 1945, another brewery stepped up and used the Yankees as a prime marketing tool. Yankees fans certainly saw a lot of Ballantine Beer, with an ad (“It’s a HIT! Ballantine Beer & Ale”) and its distinct three-ring sign (representing Purity, Body and Flavor) on the Yankee Stadium scoreboard. Ballantine was also responsible for one of baseball’s most famous calls: when a Yankee would homer, broadcaster Mel Allen would call it as a “Ballantine Blast.” Ballantine even had a jingle to promote its relationship with baseball:

Baseball and Ballantine

Baseball and Ballantine.

What a combination,

All across the nation

Baseball and Ballantine!

Schaefer Beer and the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Ebbets Field scoreboard was famous for its Schaefer Beer sponsorship, with the h and the e lighting up to indicate hit or error. Schaefer Beer, a Brooklyn institution, had been shut out of Ebbets Field and Brooklyn Dodgers broadcasts by Branch Rickey. Rickey, sometimes called “the Deacon” because of his Methodist faith, didn’t believe in pushing beer at the ballpark. When he left after the 1950 season, Walter O’Malley signed Schaefer on a $3-million sponsorship, complete with the interactive scoreboard and plenty of pitches on game broadcasts. Above: a very young Vin Scully promoting sponsors Schaefer Beer and Lucky Strikes.

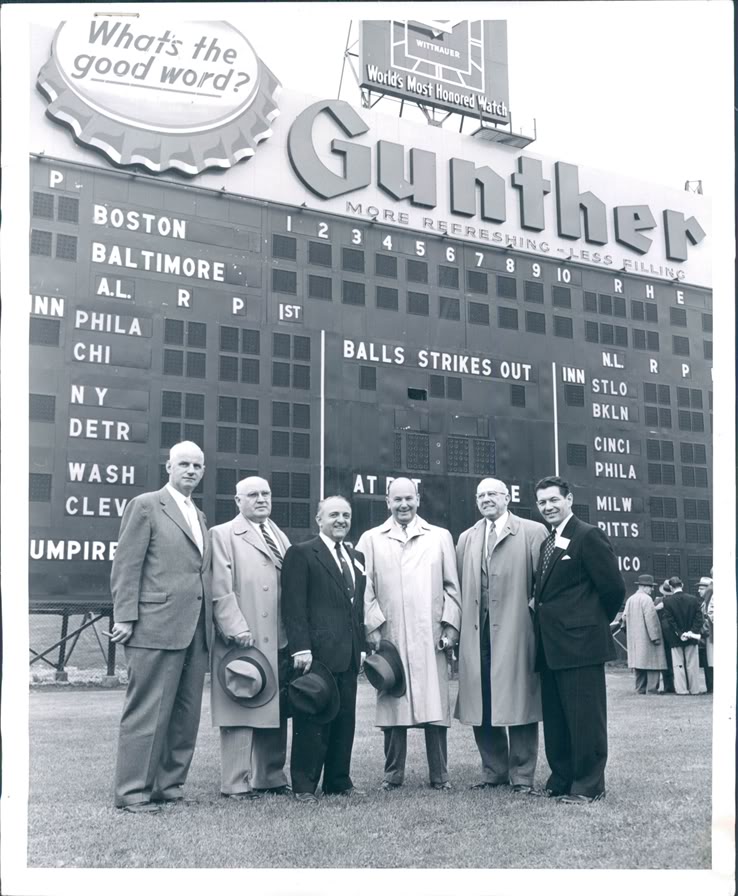

Gunther Beer and the Baltimore Orioles. Even though National Brewing Company owner Jerold Hoffberger owned the Orioles, a rival controlled the Memorial Stadium scoreboard. In May 1954, what was billed as the largest scoreboard in the world was installed at Memorial Stadium upon the arrival of the Orioles, a move underwritten by Gunther Beer. Various ad slogans were used—“What’s the good word?,” “What a Wonderful Beer,” and, finally, “Happiest Hit in Beer,” with the HIT lit up (or not) after a scoring decision—but Gunther was eventually replaced when the brewery was sold to Hamm’s. Eventually National Brewing became the scoreboard sponsor at Memorial Stadium.

Budweiser and the Chicago Cubs. It wasn’t that long ago that the best-selling beers in Chicago came from Wisconsin and Minnesota, with Milwaukee’s Schlitz, St. Paul’s Hamm’s, Huber’s Augsburger and G. Heileman’s combo of Old Style and Special Export among the market leaders. That all changed when Anheuser-Busch led a major offensive to boost Budweiser’s presence in the Chicago market. How did they accomplish that? By being a major sponsor of Cubs broadcasts on WGN-TV and enlisting Harry Caray in the marketing efforts. When WGN-TV started broadcasts Cubs games nationally on cable, Wrigley Field was presented as a sun-drenched nirvana, paving the way for the party atmosphere that exists today. Producer Arne Harris never missed a chance to show an attractive young woman in the bleachers drinking a Bud—shots always appreciated by Caray. Today, Budweiser is the major beer sponsor for Wrigley Field.

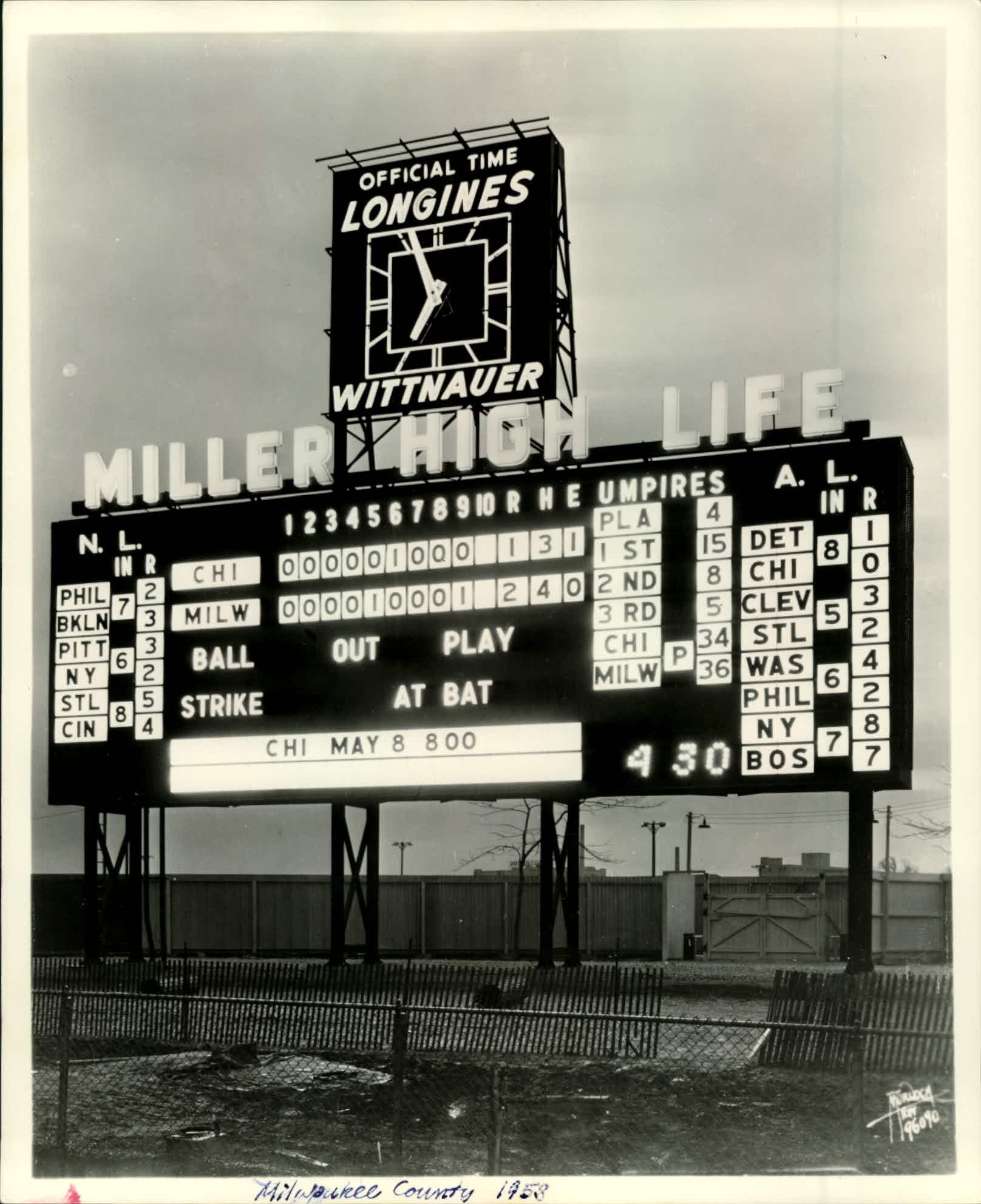

Miller High Life and the Milwaukee Brewers. If you’ve got the time, we’ve got the beer, goes the iconic Miller High Life jingle. The hometown Miller Brewing has always had a tight relationship with the Milwaukee Braves and the Milwaukee Brewers, both as a major signage sponsor and naming-rights partner on Miller Park. (Heck, you can see the Miller Brewery from Miller Park.) And when Miller sought to promote its new Lite Beer, Brewers broadcaster Bob Uecker was tapped to star in multiple television commercials. Uecker had a national profile by that time thanks to television exposure, but his fame rose further thanks to one simple line: “I must be in the front row!” The Brewers later installed obstructed-view Uecker seats at Miller Park, as well as a statue of Uecker in the very last row of Section 422.

Today, you still have some long-standing relationships between breweries and baseball, like Anheuser-Busch and the St. Louis Cardinals. But today Anheuser-Busch is just one cog in the international AB InBev machine headquartered in Belgium, and Miller Brewing is part of Molson Coors Brewing, with headquarters in Denver and Toronto. Today you’re just as likely to see an independent regional brewery like Summit Brewing well-represented at an MLB ballpark like Target Field. And while every MLB ballpark features a good assortment of macrobrews and microbrews, gone are the days when national advertising campaigns were built around beer and baseball.