If you want a stark look at how ballparks have evolved, let’s go back 50 years and review the MLB facilities in play for the 1965 season — the dawn of modern ballpark design, when the Astrodome and Shea Stadium were on the cutting edge.

The ballparks used that season reflected the same sort of transition felt in the whole of American society: tradition versus the cutting edge, the status quo versus the future. For the most part, in the ballpark world you had the new and the old and very little in between. Here’s a list of the 19 ballparks used in the 1965 MLB season. (Why 19? Because the Dodgers and Angels shared Dodger Stadium.)

1965: Astrodome

1964: Shea Stadium

1962: Dodger Stadium, D.C. Stadium

1961: Metropolitan Stadium

1960: Candlestick Park

1955: K.C. Municipal Stadium (renovated older facility)

1953: County Stadium

1950: Memorial Stadium (renovated older facility)

1932: Cleveland Municipal Stadium

1923: Yankee Stadium

1914: Wrigley Field

1912: Crosley Field, Tiger Stadium, Fenway Park

1910: Comiskey Park

1909: Forbes Field, Connie Mack Stadium, Busch Stadium (formerly Sportsman’s Park)

Talk about extremes! On the one hand, you had old ballparks dating back to the emergence of concrete and steel construction in sports facilities, with eight ballparks over 50 years old and already showing their ages. They were similar in terms of design: Zachary Taylor Davis and Osborn Engineering worked on several of these old ballparks, and owners were pretty keen on borrowing successful construction elements from other MLB owners. By 1965 owners were seeking to abandon these old ballparks: Ebbets Field, League Park and the Polo Grounds were gone, Braves Field was mostly gone, and Forbes Field, Connie Mack Stadium, Busch Stadium and Crosley Field would be gone in a matter of years. And there were the ballparks that were old in spirit, if not age: the County Stadium and the Met were born aged (the most celebrated part of the Met: the lack of supports for the cantilevered upper deck, a total feat of engineering), and Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium and Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium just renovated old parks.

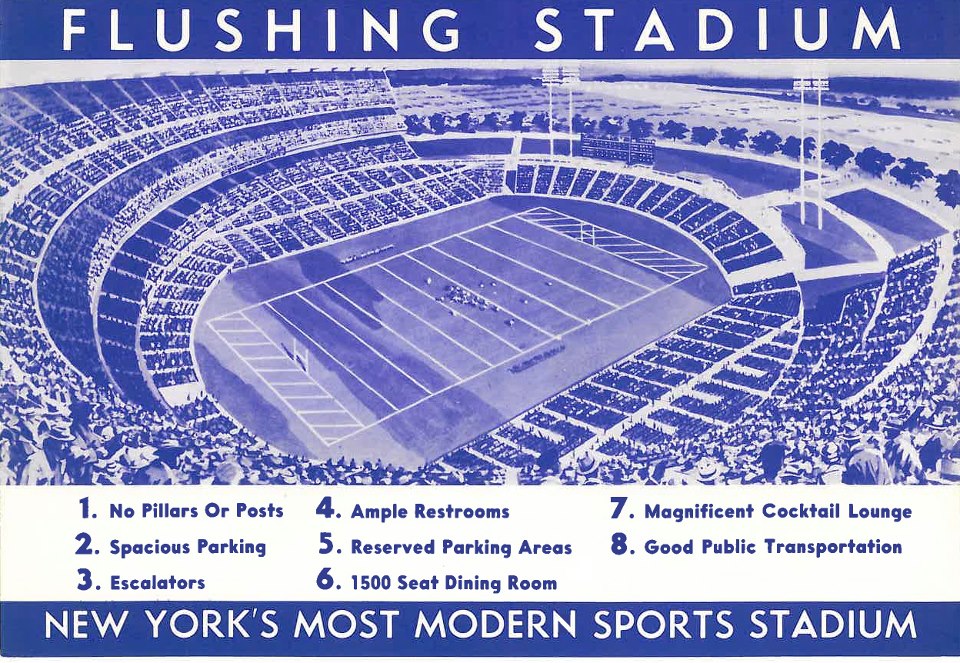

On the other hand, you had five newer ballparks that for one reason or another were considered state of the art and projected as the future of sporting facilities. D.C. Stadium — later named RFK Stadium, still standing and used for MLS soccer — was the first stadium designed explicitly both for baseball and football. Candlestick Park‘s original configuration was for baseball (it would be later changed after the 49ers left Kezar Stadium), with lots of reinforced concrete and a very open design — California cool, as it were. Shea Stadium extended the multiuse theme with lots of fan amenities, including escalators, restaurants and cocktail lounges, as well as high-tech touches like the huge scoreboard with a projection screen. Dodger Stadium combined elements of mid-century modern with an open design that still works well.

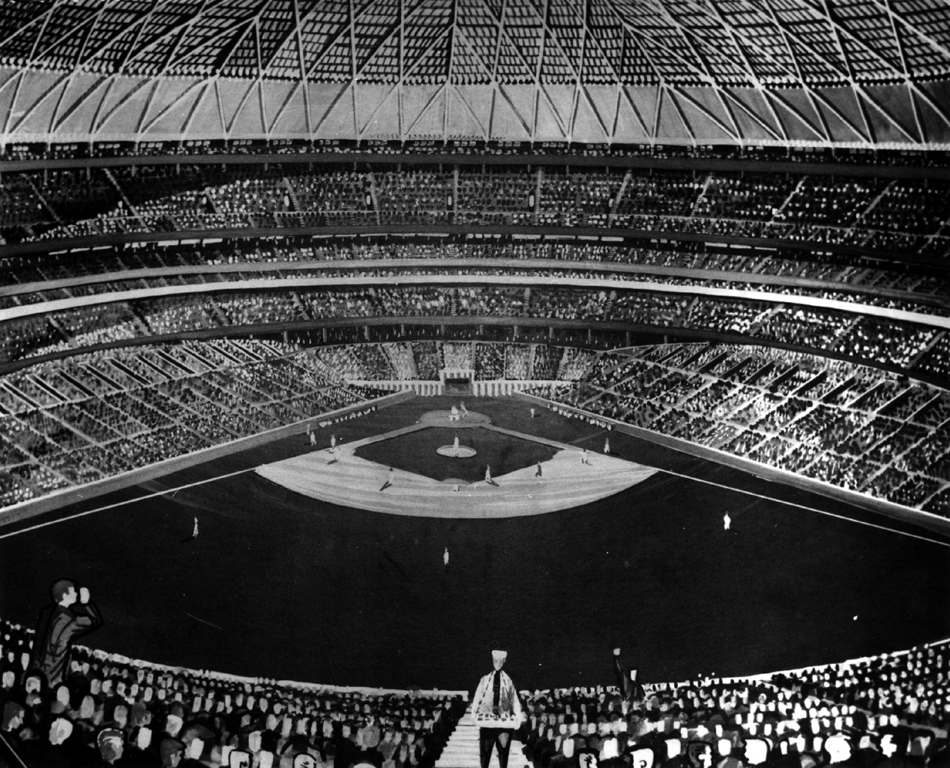

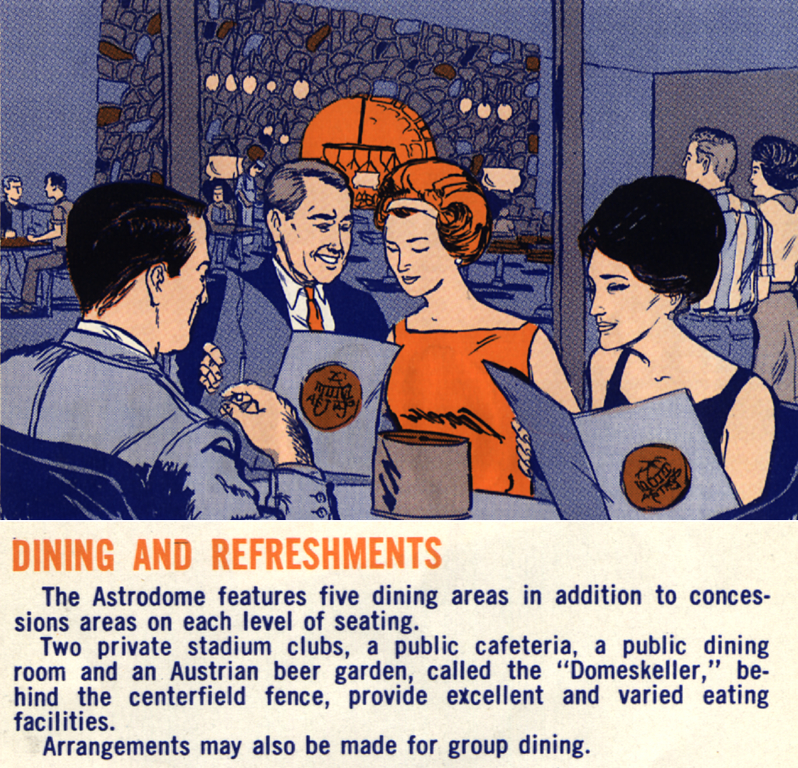

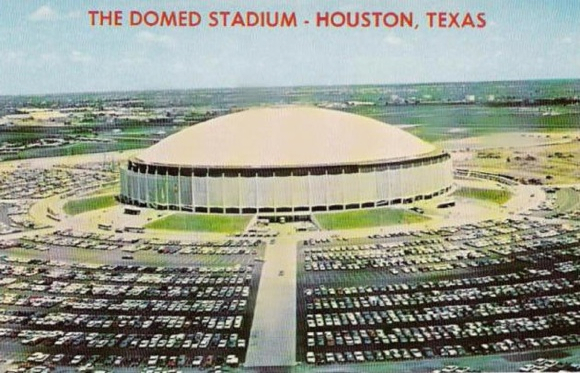

And then there’s the Astrodome, the first enclosed ballpark with all the flair that Judge Roy Hofheinz and crew could give us. With an exciting animated scoreboard, air conditioning, excessive design, rococo suites, multiple restaurants and an apartment for Judge Hofheinz that included a Presidential Suite, the Tipsy Tavern (where everything was purposely askew as to confuse drinkers), a chapel and a shooting range, the Astrodome was truly the Eighth Wonder of the World. It was its own ultimate destination. (A rendering for the Astrodome is at the top of this page.)

If you were to poll ballpark designers at the time — and there weren’t many, with Praeger-Kavanagh-Waterbury a leader in the field with the design of Shea Stadium and Dodger Stadium, but nothing like the sports-architecture industry of today — we’re guessing the Astrodome and Shea Stadium would have been considered the models for future ballpark design. We would see several enclosed ballparks over the next 20 years in the form of the Kingdome, the Metrodome and Tropicana Field, and we would see several other multiuse facilities as well, including Three Rivers Stadium, Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum, Riverfront Stadium and the second Busch Stadium.

But, as turns out, multiuse stadiums would end up being a dead end, as the economics and aesthetics of sports dictated separate facilities for MLB and pro/college football teams with sightlines and layouts specific to the game on the field. Fixed roofs were replaced by retractable-roof ballparks, whether it be more analogous to a covering (in the case of Safeco Field) or an enclosed structure a la Miller Park. And, with the opening of Oriole Park at Camden Yards, we saw a totally original approach to ballpark design, a retro look that was also efficient in managing crowds and expectations. Of course, in 1965, there was no need for retro: the world wanted space travel and flying cars, and fans had little desire to look back when the future was at hand.

So what’s the lesson as we review 1965 MLB ballparks? The future is exceedingly hard to predict, but you knew that: we’re still waiting for the flying cars promised us in the 1960s. In many ways, the Astrodome and Shea Stadium ended up influencing ballpark design to this day for one simple reason: Whereas in the past ballparks were feats of engineering (how to cram 40,000 fans into a small space while getting them in and out in a timely fashion), modern ballparks are achievements of design as well. The Astrodome might have been an engineering miracle, but today it’s remembered for the audacious design, those excessive suites, that space-age optimism. Dodger Stadium still exudes that mid-century cool. And Shea Stadium, that highlight of the World’s Fair and the embodiment of forward thinking, is still fondly remembered by a surprising number of Mets fans who remember that optimism embodied in the era. (It wouldn’t last, alas.) When we look back at 1965 MLB parks, we can see the first attempts to create a memorable ballpark experience through design — and there’s not a ballpark, football stadium or arena created these days without that emphasis on design.