He designed two of the most iconic sporting facilities in America, both over 100 years ago. Meet Zachary Taylor Davis, a peer of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, and the architect behind Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park.

In the earliest days of professional baseball, there was no such thing as sports architecture, and most of the designers of the first wave of concrete-and-steel facilities are by and large forgotten today. No one celebrates Charles Wellford Leavitt as the architect of Forbes Field, despite a career that included Belmont Park and other well-known racetracks, as well as being a noted landscape architect. The firm of William Steele and Sons, who built Shibe Park, was chosen by Ben Shibe because of its expertise in steel-based construction, not because of any ballpark experience. And while Osborn Engineering had a hand in many early ballparks, it was because of the engineering background, not the design licks.

David, however, came from a slightly different background, working in the fertile Chicago architecture world at the turn of the century. A native of nearby Aurora and a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, Davis apprenticed as a draftsman for six years at various Chicago architectural firms, including the influential Adler and Sullivan firm. Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan were Chicago architectural pioneers, helping to create the Prairie Style that would come to dominate Midwest architecture for decades. Those were heady times to be a Chicago architect, with plenty of talent in the Windy City: Frank Lloyd Wright’s time at Adler and Sullivan overlapped with Davis’s, and architects like Daniel Burnham were plying their trade in other offices.

And what could be more American than ballpark design? Despite the roots in engineering, some high-profile architects have tackled ballpark projects: Cass Gilbert, who designed the iconic Woolworth Tower in New York City, once designed a ballpark for the St. Paul Saints; Robert A.M. Stern worked on the 1996 renovation of Angel Stadium; and both Norman Bel Geddes and R. Buckminster Fuller took shots at a domed Brooklyn Dodgers ballpark.

Although Davis ended up in-house at Armour & Co. designing meat-packing plants, he took on outside work: courthouses, residences and churches. He also took on an interesting project for Charles Comiskey, then establishing himself as the king of Chicago baseball: a new ballpark on the South Side. Comiskey was a disruptive force in the professional baseball world, helping to form the upstart American League in 1899 and moving his St. Paul Saints to Chicago. Comiskey built South Side Park to house his White Stockings, but the team soon outgrew that modest facility, despite a few expansions and modifications.

By December 1908 Comiskey was ready to invest in a new ballpark, and after rejecting the South Side Park area because he couldn’t acquire additional land, Comiskey announced he had purchased the old Players’ League Brotherhood Park site between 34th and 35th streets, bounded by Westworth Avenue to the east and Shields Avenue to the west, for $150,000. At 15 acres, Comiskey reasoned he had room for a new ballpark as well as a winter amusement park. It was a challenging site: the area had once been a city dump, and it was within smelling distance of the famed Chicago Stockyards, once the largest livestock market and meat processing plant in the world.

Though he had experience in ballpark design and would be deeply involved in mapping out the “Baseball Palace of the World,” Comiskey sent Davis, pitcher Ed Lynch and Davis’s assistant, Karl Vitzhum (who previously worked under Burnham) on a tour of Major League ballparks to scope out what worked and what didn’t. Comiskey, who worked as his own contractor on South Side Park, had some definite ideas on what he wanted to see in a new ballpark: a well-drained field and a layout where fans accessed the upper areas of the grandstand via ramps, not stairs. Davis settled on Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field as a model and pitched a concrete-and-steel facility seating 30,000 (later expanded to 35,000), with the playing field on the same location as the old Brotherhood Park diamond. Davis’s design featured a grand entryway based on the Roman Coliseum and a huge playing field: 450 feet to center field, 350 feet down each line, later altered to 420 feet to center and 363 feet down each line.

Though they didn’t call it “value engineering” at the time, Comiskey and Davis made changes to the design when bids came in $200,000 over the budgeted $500,000, including the substitution of wood for concrete in the bleacher sections. Later changes were made due to aesthetics: Comiskey eliminated a third deck after his own visit to Forbes Field, and the Roman Coliseum exterior was scaled back to a simpler design, albeit one with Prairie School touches – befitting Chicago architecture and the time Davis spent working under Louis Sullivan.

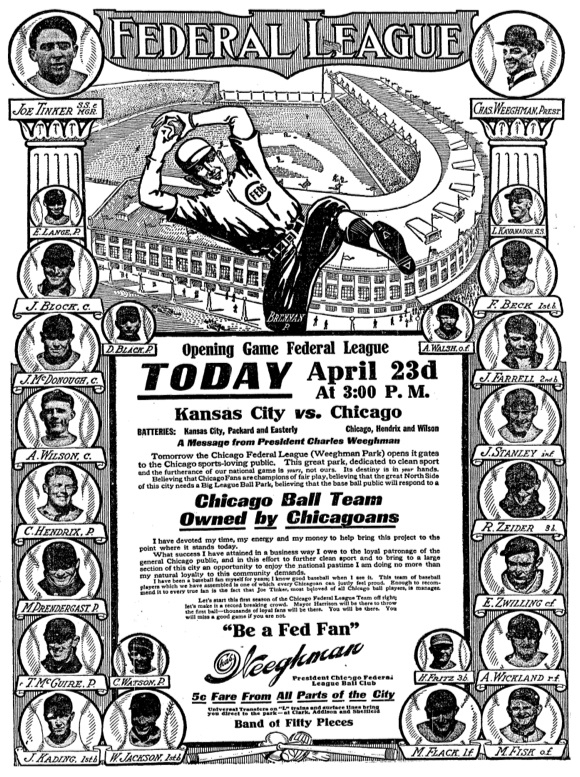

White Sox Park – with a name change to Comiskey Park three years later – was an instant success, and Charlie Comiskey was the toast of Chicago baseball. By 1910 the White Sox and the Cubs were in an epic battle for the hearts and minds of Chicago baseball fans, both drawing over 500,000 fans a season and the Cubs winning 104 games that season. Despite both fans drawing well for the era, local restaurateur Charles Weeghman was recruited to launch a Federal League team in the thriving Windy City. The upstart Federal League It’s likely Weeghman and Davis were in the same circles of nouveaux riches Chicagoans: Davis landed several house and church commissions for wealthy Chicagoans, and Weeghman had ascended from coffee boy at a Loop restaurant to owning 15 lunch counters in the city. When Federal League President James A. Gilmore recruited Weeghman to launch the Chi-Feds (or Chifeds) for the 1914 season, Weeghman jumped at the chance to own a professional baseball team.

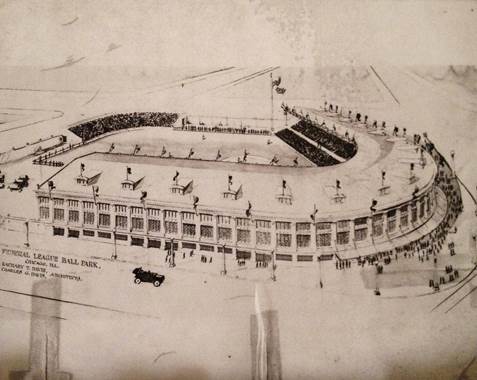

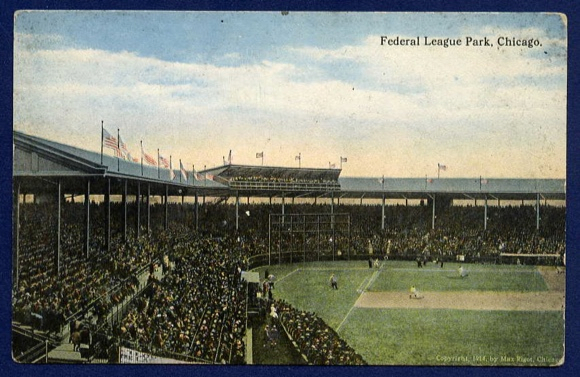

Leasing land at Clark and Addison Streets in the residential north side of the Chicago, Weeghman recruited Davis to design a ballpark. Davis’s original design – which eschewed the enormous proportions of Comiskey Park (pushed by the former pitcher, Ed Lynch) – ended up being approved by Weeghman with few changes, and the Blome-Sinek Company constructed Weeghman Park for the Chi-Feds, launching for the 1914 season.

Pretty amazing when you consider the groundbreaking for Weeghman Park was March 4, 1914. But you must remember that the Weeghman Park of 1914 was merely the core of modern Wrigley Field: that first ballpark was a single-decked facility with a canopy (no second deck) and only extended part of the way down the left-field line. The capacity was only 20,000: 18,000 in the grandstand, 2,000 in the “two-bit” bleachers. Davis’s design cost Weeghman $250,000 – a huge sum for the day, but far less what other team owners were paying for larger and more palatial ballparks. And while Davis oversaw changes to Weeghman Park for the 1915 season – mostly involving the expansion of the right-field bleachers – more substantive expansions were not to be.

The Federal League would end up going under after the 1915 season, but Weeghman bought out the Chicago Cubs and moved the team to the north side. The Federal League had battered the Cubs, whose attendance plummeted at West Side Grounds after the emergence of the Chi-Feds. And while Cubs attendance rose at Weeghman Park, the finances didn’t work in Lucky Charlie’s favor: he sold the team and the ballpark three years later to William Wrigley, the gum magnate who ended up implementing the rest of the Zachary Taylor Davis design over time: the left-field seating was extended all the way down the line in 1923, the upper deck was built in the 1927-28 time period (both under Davis’s supervision), and the bleachers were renovated and expanded in 1937, complete with the iconic scoreboard still viewed today.

Davis’s ballpark vision would end up being implemented in Brooklyn, where the Federal League’s Brooklyn Tip-Tops hired Davis as a consultant to recreate Weeghman Park in a reconstruction of Washington Park, former home to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Charles Ebbets had moved his Dodgers to Ebbets Field – a ballpark of his own design, given his background as a draftsman and architect – and had demolished the team’s former home, Washington Park, to deter another pro team from moving there. Undeterred, the Ward Brothers (owners of Tip Top Bread; hence the team name) constructed a new ballpark for their Federal League team. They were more successful as bakers than baseball entrepreneurs: as noted, the Federal League went under after the 1915 season, but their firm, Continental Baking Company, ended up creating both Wonder Bread and Hostess Twinkies. And Washington Park ended up being torn down soon after the Federal League went under, though for many years a wall that was part of that ballpark stood.

Later in his career Davis submitted a design for a new waterfront facility, Municipal Grant Park Stadium, to honor World War I veterans, a project that became Soldier Field. Though Davis and William F. Kramer didn’t win the competition, the design they submitted ended up looking a lot like the winning submission.

Renderings courtesy of the Zachary Taylor Davis website, which is worth checking out.