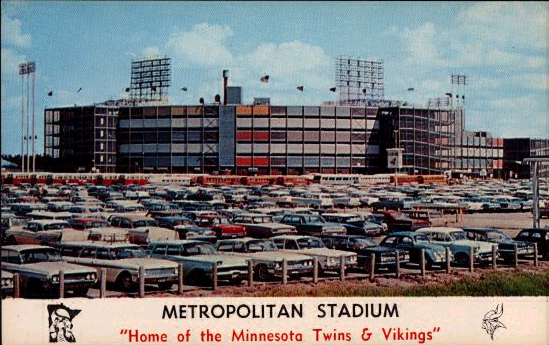

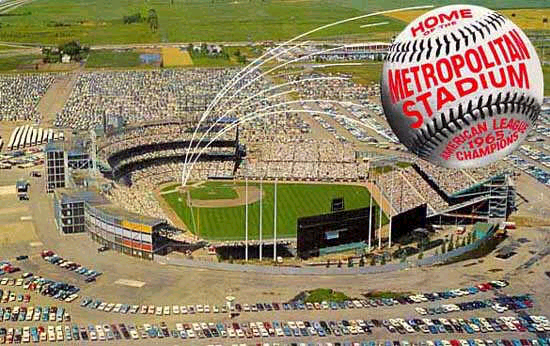

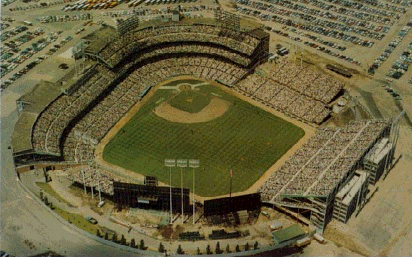

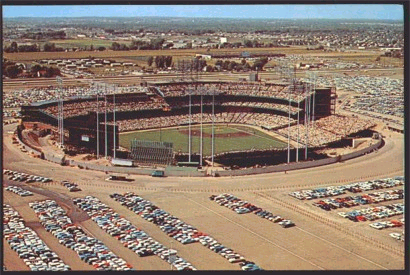

Metropolitan Stadium became a major-league ballpark on April 21, 1961, when 24,606 fans showed up for the Twins’ home opener. It took some time for Metropolitan Stadium to make the 40,000-seat level promised to Calvin Griffith when he moved the Senators — 1964, to be exact — but at the beginning the Met was regarded as one of the nicest ballparks in the major leagues, if only for its newnewss. Still, it was never really beloved by the more casual Twins fans. Part of the reason was the hodge-podge design: it was built in sections and it showed. Some of the sections were three decks, some were two decks, and some were a single deck. It was perhaps the most open-air ballpark ever constructed, as the only sheltered part of the ballpark was the back of the grandstand, covered by the cantilevered deck above them.

Seating: 30,637 (1961), 40,000 (1964), 45,919 (1975)

Original cost: $8.5 million

Metropolitan Stadium was dedicated in September 1955 and opened on April 24, 1956 as the home of the Class AAA Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, but it was never built to be a minor-league stadium. In the mid-1950s, the Twin Cities civic leaders considered themselves ready to enter the “big leagues” and launched a pursuit of major-league football and baseball teams. To further these efforts, the Baseball Committee of the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce paid $478,899 for 164 acres of farmland in rural Bloomington, to be used to build a baseball stadium for a major-league ball team.

Minneapolis’s pursuit of a team predated this commitment to a stadium, however. This was an era when local sportswriters acted in several different capacities, and one of the leaders to bring baseball to Minnesota was Charles O. Johnson, the executive sports editor of the Minneapolis Tribune (now the Minneapolis Star Tribune). On the behalf of local business leaders, Johnson made inquiries at the baseball commissioner’s office in New York in the early 1950s about possible expansion plans. At the same time the Boston Braves of the National League moved to Milwaukee, which opened the possibility that other franchise shifts could be forthcoming.

The first target was Bill Veeck, who had decided that competing with the deep pockets of Anheuser-Busch was too much and wanted to move his St. Louis Browns. Veeck wanted to move the Browns to Baltimore — which was indeed where they ended up — and pretty much ignored all requests to meet with Twin Cities officials. However, the play for the Browns caught the attention of other owners. Overtures were made to Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants, and the creditors of the Philadelphia Athletics, who controlled the franchise. The deal with the Athletics fell through when Twin Cities leaders decided to focus on building a stadium and then attracting a team after failing to raise $1.6 million as a down payment on the team. Arnold Johnson ended up buying the Athletics and rebuilding Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium for the 1955 season. It was then that the Baseball Committee of the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce decided to go ahead with a ballpark construction. However, the ballpark almost did not come to be, as initial efforts to raise $4.5 million in private capital for the ballpark fell short. Only after a concentrated effort by 50 business leaders was the necessary money raised. Still, the committee was living a hand-to-mouth existence: the groundbreaking was initially delayed because the committee had not paid Paul Gerhardt, a farmer who had grown onions, melons and sweet corn on the 50-acre parcel he was selling to the committee, his $122,000. Gerhardt lined up his farm machinery in protest along what would become the first-base line and refused to move until he had a check in hand.

With a new ballpark — one that Horace Stoneham had personally advocated to Minneapolis leaders, incidentally, saying that he wouldn’t consider a move to Minnesota until a new stadium was constructed — the New York Giants then negotiated a move to Minneapolis. The Giants knew the area well (it owned the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, who would be the initial tenant of the Met) but at the last minute Horace Stoneham spurned both the Twin Cities and the borough of Manhattan — which had proposed a new 110,000-seat stadium over the New York Central railroad tracks, on a 470,000-foot site stretching from 60th to 72nd streets on Manhattan’s West Side — and accompanied the Dodgers to the West Coast, setting up shop as the San Francisco Giants.

Next on the suitor list was the Cleveland Indians. Nate Dolan, the majority owner of the Indians, wanted to move the team, but the team’s long-term lease for Municipal Stadium made a move unfeasible.

Finally, the Washington Senators were in play. Although the late Clark Griffith supported efforts to bring baseball to Minnesota, he said that he would never move the Senators from Washington. The feeling was not shared by his nephew Calvin Griffith, who (along with his sister Thelma Haynes) assumed ownership of the Senators when Clark Griffith passed away in 1955.

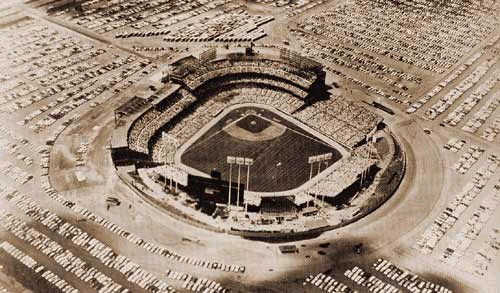

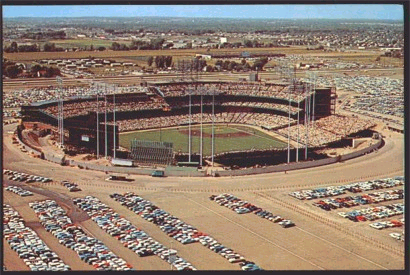

In the meantime, the stadium was occupied by the Minneapolis Millers, who moved to the Met from the team’s old Nicollet Park location. The first game at the Met was played on April 24, 1956, with the Millers taking on the Wichita Braves. Over 18,000 fans showed up in 45-degree weather to see the new park. It was a unique stadium at the time: the main three-decked grandstand was complete and wrapped from third base to first, but there were only temporary bleachers down the third-base line and only fences in the outfield. The grandstand would be extended down to the outfield when the Twins moved in 1961, and in 1965 the left-field pavilion was build by the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings. At the time, its cantilever design was considered revolutionary, with no poles, or pillars to obstruct any views.

Griffith was unwilling to move the Senators during this time, but something pressed his hand: Branch Rickey’s Continental League which was being taken seriously as a competitor to the American and National Leagues. There were some big names involved with the Continental League — its chairman was William Shea, for whom Shea Stadium was named — and ironically it was formed because both the Giants and the Dodgers moved away from New York City, prompting civic leaders there to declare that the need for baseball in the five boroughs. By July 1960 the Continental League had awarded franchises to New York, Houston, Toronto, Denver, and Minneapolis/St. Paul, but two weeks later the Continental League died when MLB said that it would expand into four new territories in an orderly fashion. (That’s how the Mets and the Houston .45s came to be.) Since MLB had basically promised a team to Minneapolis/St. Paul, this made it safe for Calvin Griffith to seek a move to the area. Griffith’s demands were not unreasonable: $250,000 in moving expenses, financial help from the banks, a guarantee of a 40,000-seat stadium, and 750,000 paid fans for each of the first three years. These terms were accepted by Twin Cities civic leaders, and the team move was announced on October 26, 1961. At the same time, expansion franchises were awarded to Los Angeles and Washington.

The team moving from Washington was originally to be called the Twin Cities Twins, and original logo and uniform designs reflected these plans. When Minnesota leaders persuaded Griffith to use the Minnesota Twins name (which was unheard of at the time; up until then team names reflected metropolitan areas and not entire states), Griffith decided to keep the original designs, which is why Twins caps have a “TC” as the logo.

Metropolitan Stadium became a major-league stadium on April 21, 1961, when 24,606 fans showed up for the Twins’ home opener. It took some time for Metropolitan Stadium to make the 40,000-seat level promised to Griffith — 1964, to be exact — but at the beginning the Met was regarded as one of the nicest stadiums in the major leagues. Still, it was never really beloved by the more casual Twins fans. Part of the reason was the hodge-podge design: it was built in sections and it showed. Some of the sections were three decks, some were two decks, and some were a single deck. It was perhaps the most open-air stadium ever construction, as the only sheltered part of the stadium was the back of the grandstand, covered by the cantilevered deck above them.

Because of the open design, the Met was regarded as a hitters’ ballpark because of the many wind-aided popups that ended up as home runs. While sluggers like Harmon Killebrew and Bob Allison didn’t need any help in getting the ball out of the yard, others did — most famously Orioles pitcher Mike Cuellar, a career .089 hitter whose grand-slam home run in the league championship series in 1970 was certainly aided by the wind.

The left-field bleachers were added by the NFL’s Vikings and were on a different scale than the rest of the park (the grandstand was cantilevered; the left-field bleachers were not). It was difficult to move between different sections of the park; more often than not you were forced to actually leave the stadium if you wanted to go from the bleachers to the grandstand, and there was a never a clear path when you wanted to move from Point A to Point B. When the Metrodome was announced as the future home of the Twins, a “Save the Met” organization was formed, but to no avail (the group was really pro-outdoor baseball; saving the Met was an afterthought). Part of the fondness of the Met was really a fondness for the Twins teams of the 1960s and early 1970s, when stars like Killebrew, Jim Kaat, Tony Oliva, Rod Carew, Bert Blyleven, Zolio Versalles and Bob Allison thrilled Met Stadium crowds, and the other part of the fondness was for the expansive parking lots surrounding the stadium — perfect for tailgating before and after games.

Most folks attending Twins games remember the multi-story scoreboard in right-center field. By today’s standards, it wasn’t much of a scoreboard: it combined ads, batting lineups, and a Longines clock on the top. (However, by comparison, this scoreboard was more informative than the skimpy scoreboards in the Metrodome.) For most of the Met’s history the bullpens were located in front of the scoreboard.

The final game played at the Met was on Sept. 30, 1981 (the Twins lost 5-2 to the Kansas City Royals, by the way), with the Twins moving to the Metrodome for the 1982 season. By the end, though, the Met had seen better days; conspiracy theorists in the Twin Cities argued that the Metropolitan Sports Commission — which by then was in charge of the stadium — purposely scaled back on maintenance to make a new stadium more appealing. In 1981, the third deck was considered a safety hazard because of broken railings overlooking the left field bleachers, and the area was cordoned off.

Today, there are a few markers to commemorate Met Stadium at the Mall of America, which eventually went up in the same site. Killebrew Drive runs along the south side of the Mall. The location of the Met’s home plate is marked in Nickelodeon Universe, while a marker in the northern wall marks where Killebrew hit the longest home run in Metropolitan Stadium history: 520 feet on June 3, 1967. (No marker to commemorate Killebrew’s 500th home run, hit on Aug. 10, 1971 to the left-field bleachers.) Interestingly, some local business leaders (goaded on by influential Star Tribune columnist Sid Hartman) floated the idea of putting a new Twins stadium in the former Met Center location north of the former Met Stadium site and connect the new stadium to the Mall of America, but there was a clause in the land sales agreement that prohibited the use of the land for a stadium. In addition, with the expansion of nearby Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport, the site would probably not pass muster with federal aviation authorities, as it’s directly in a flight path.

METROPOLITAN STADIUM STATS

| Dimensions | |||||

| Year | LF | LC | C | RC | RF |

| 1961 | 329 | 402 | 412 | 402 | 329 |

| 1962 | 330 | 402 | 412 | 402 | 330 |

| 1965 | 344 | 435 | 430 | 435 | 330 |

| 1968 | 346 | 430 | 425 | 430 | 330 |

| 1975 | 330 | 410 | 410 | 430 | 330 |

| 1977 | 343 | 406 | 402 | 410 | 330 |

METROPOLITAN STADIUM ATTENDANCE

| Year | Attendance | Average | Rank in League | Record | Standing | |

| 1961 | 1,256,723 | 15,515 | 3rd out of 10 | 70-90 | 7 | |

| 1962 | 1,433,116 | 17,477 | 2nd out of 10 | 91-71 | 2 | |

| 1963 | 1,406,652 | 17,366 | 1st out of 10 | 91-70 | 3 | |

| 1964 | 1,207,514 | 14,726 | 3rd out of 10 | 79-83 | 6 | |

| 1965 | 1,463,258 | 18,065 | 1st out of 10 | 102-60 | 1 | |

| 1966 | 1,259,374 | 15,548 | 2nd out of 10 | 89-73 | 2 | |

| 1967 | 1,483,547 | 18,315 | 2nd out of 10 | 91-71 | 2 | |

| 1968 | 1,143,257 | 14,114 | 4th out of 10 | 79-83 | 7 | |

| 1969 | 1,349,328 | 16,658 | 3rd out of 12 | 97-65 | 1 | |

| 1970 | 1,261,887 | 15,579 | 3rd out of 12 | 98-64 | 1 | |

| 1971 | 940,858 | 11,910 | 5th out of 12 | 74-86 | 5 | |

| 1972 | 797,901 | 10,782 | 7th out of 12 | 77-77 | 3 | |

| 1973 | 907,499 | 11,204 | 10th out of 12 | 81-81 | 3 | |

| 1974 | 662,401 | 8,078 | 12th out of 12 | 82-80 | 3 | |

| 1975 | 737,156 | 8,990 | 12th out of 12 | 76-83 | 4 | |

| 1976 | 715,394 | 8,832 | 12th out of 12 | 85-77 | 3 | |

| 1977 | 1,162,727 | 14,534 | 11th out of 14 | 84-77 | 4 | |

| 1978 | 787,878 | 9,727 | 13th out of 14 | 73-89 | 4 | |

| 1979 | 1,070,521 | 13,216 | 11th out of 14 | 82-80 | 4 | |

| 1980 | 769,206 | 9,615 | 14th out of 14th | 77-84 | 3 | |

| 1981 | 469,090 | 7,690 | 14th out of 14th | 41-58 | 7 |