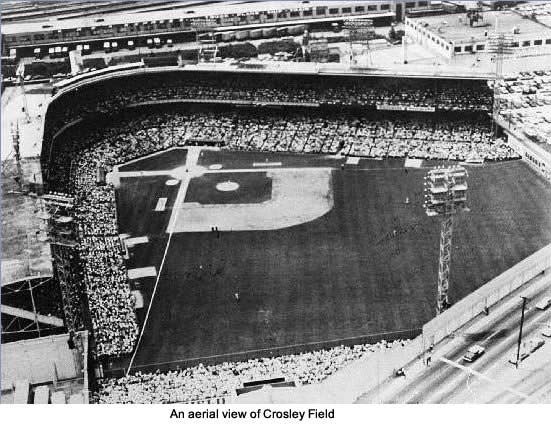

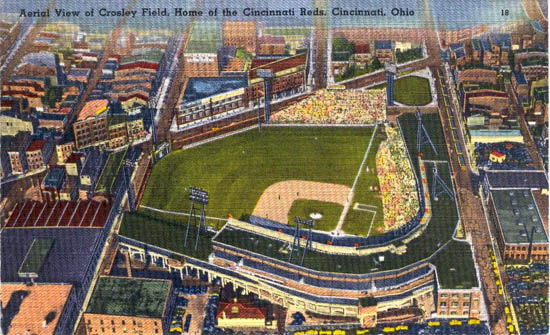

When baseball fans think about Cincinnati, they think about firsts. The first professional baseball team. Charter members of the National League and the American Association. The first night game. The first pitch of the season. For six decades this city of baseball firsts played its games at the “old boomerang at Findlay and Western,” Crosley Field. The park was a green oasis amidst the smokestacks and warehouses of Cincinnati’s west end. Crosley was intimate and unpretentious, and its many stories and unique characteristics gave the average fan a lot of baseball to experience.

Dating back to 1884, the Reds played baseball at the intersection of Findlay Street and Western Avenue. League Park was the first to open there, and as happened with most wooden ballparks of the day, it burned to the ground. In 1893, League Park was rebuilt, columned, expanded, and renamed The Palace of the Fans. The Palace of the Fans resembled a Greek temple, with an extravagant façade and opera-style private boxes. Alas, it too burned, in 1911, and gave way to Redland (later Crosley) Field.

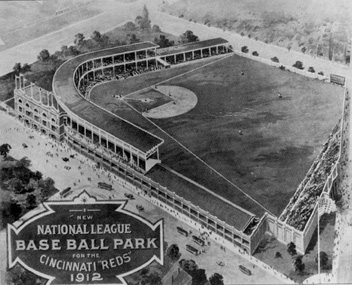

Redland Field, named to honor the traditional color of Cincinnati baseball teams, opened its gates on April 12, 1912. The hometown Reds rallied from a 5-0 deficit to defeat the Cubs 10-6. Redland was built for $225,000 and was another of the many classic steel and concrete parks constructed during the first ballpark boom era of 1909-1923. The red brick, boomerang-like edifice was originally built featuring a covered double-decked grandstand that wrapped around home plate and extended about thirty feet past both first and third base. Single-decked pavilion seating continued into both outfield corners. Total seating capacity was just over 20,000. It was one of the smallest-capacity parks when it was built and remained one of the smallest in the league throughout its six-decade history. The outfield bleachers only held 4,500 fans, all in right field. In fact, permanent seating was never employed in left and center field.

Despite the cozy confines for the fans, the park played big. It was a pitcher-friendly 360 feet to left, 420 feet to center, and 360 feet to right. Throughout its early years, Redland was said to have the hardest and fastest playing surface in the league. (Coincidentally, and unfortunately, years down the road at Riverfront Stadium, the Reds would become the first outdoor team to play its home games on the slick, billiards table-like artificial turf.) Before the 1927 season, responding to the popularity of Babe Ruth and the Home Run era, the Reds turned their playing field and moved home plate out 20 feet, creating better dimensions for sluggers (339’, 395’, 366’).

Despite the cozy confines for the fans, the park played big. It was a pitcher-friendly 360 feet to left, 420 feet to center, and 360 feet to right. Throughout its early years, Redland was said to have the hardest and fastest playing surface in the league. (Coincidentally, and unfortunately, years down the road at Riverfront Stadium, the Reds would become the first outdoor team to play its home games on the slick, billiards table-like artificial turf.) Before the 1927 season, responding to the popularity of Babe Ruth and the Home Run era, the Reds turned their playing field and moved home plate out 20 feet, creating better dimensions for sluggers (339’, 395’, 366’).

By 1933 Reds owner Sid Weil lost the team to bankruptcy. The bank hired Leland Stanford “Larry” MacPhail to look after the Reds. MacPhail, cankerous and hot-tempered, would prove to be one of baseball’s great innovators. His first move was to sell the majority of the club to Powel Crosley Jr. Crosley was one of the first millionaires whose fortunes came from the new medium of direct mail, and he turned that early fortune into a media empire that included 50,000-watt radio station WLW (“the Nation’s Station”) and the first NBC affiliate. In a way, he was a predecessor of Ted Turner, buying the Cincinnati Reds for $450,000 and using team broadcasts as a way to prop up his radio and television interests. In fact, a Reds TV broadcast became the first sports program ever broadcast in color.

It was said that Powel Crosley was not a man of broad interests, and his wife complained that they did little together other than fish and watch baseball. That’s a little unfair: Crosley invented the first compact car (which was sold through department stores, not traditional dealerships), the first car radio (the Roamio), the first refrigerator with door shelving units (the Shelvador), and a bed cooling system (the Koolrest). To his credit, he gave the majority of ownership responsibilities to his younger brother Lewis (Lewis actually ran all the businesses for Powell), changed the name of the park to Crosley Field, and hired Larry MacPhail to be the general manager.

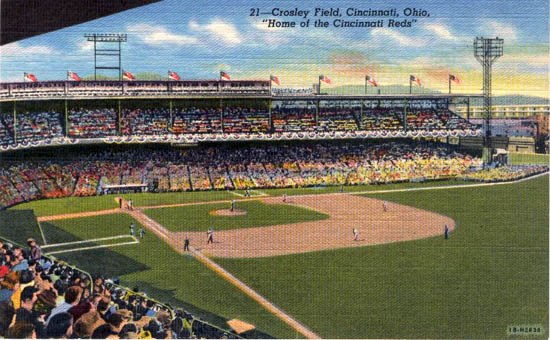

Many of the major structural renovations at the stadium happened after the new administration took over. Between the 1937-38 seasons, home plate was moved another twenty feet out (328’, 387’, 366’) and in the middle of their pennant winning season of 1939, the Reds added roofed upper decks to the left and right field pavilions. This gave Crosley Field 5,000 extra seats and the appearance it would retain for the rest of its existence.

The park that was once rented out for dance and film (in 1920 the Cincinnati Enquirer called it “immoral dancing” with “vulgar conduct between boys and girls in unlit parts of the grandstand” had some of the most unique features and landmarks in the game.

The Terrace in left field, similar to Duffy’s Cliff at old Fenway Park and Tal’s Hill in present-day Houston, was the scourge of National League outfielders. Due to an underground stream, about twenty feet out from the left-field fence, the ground sloped upward, gradually inclining until it reached the four feet grade at the wall. Thus, the left field fence measured 14’ high but was 18’ above home plate. In 1935, near the end of his career, Babe Ruth –then playing with the Boston Braves — went back on a fly ball and tripped on the incline, falling flat on his face. Ruth got up and solemnly walked off the field in disgust. He would not return to the game and retired a few days later. You can see the incline in the photo below.

Beyond the left-field fence sat the Superior Towel and Linen Service building. It was prominently visible to all in attendance and was the target of many a right-handed slugger. Perched atop the laundry was one of baseball’s most well-known signs (HIT THIS SIGN AND GET A SIEBLER SUIT — Siebler’s) gave out a total of 176 of their finest. Reds outfielder Wally Post led all hitters with 16. Willie Mays collected seven suits, tops among visiting players. The most famous home run at Crosley cleared the sign and landed in the back of a truck. It was calculated that Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi’s moon shot traveled 30 miles.

Center field at Crosley was the source of some controversy over the years. The three-story brick Crowe Engineering Company building in center was where 1950’s Reds’ skipper Fred Hutchinson would position his sign stealers. That is at least what the Cubs alleged. Also, a fluke play in center cost the Reds a potentially critical game in their pennant winning season of 1940. Street lights behind the center field fence caused such glare that canvas shields were placed on the fence to protect the batter’s eyes. The shields were then taken down for day games. Following a night game on June 5th, someone from the Reds forgot to take the shields down. In the ninth inning of a day game two days later, the Reds’ Harry Craft hit a shot that struck a shield above the center field fence. The ball fell to the ground and Craft wound up at third with a triple. Reds manager Bill McKechnie argued for thirty minutes that the call should have been a game-winning home run. Ultimately, the umpires ruled against the Reds because it was their fault, and predictably, they lost the game in extra innings by one run.

Right field was the only section of Crosley that was completely exposed to the sun and the bleacher section was thusly nicknamed the Sun Deck. A huge sun burst was painted on the rear wall. At night, naturally, the area was called the Moon Deck. (This area of seating was re-created in Great American Ball Park.) For two periods during the 1940’s and 1950’s, seats were installed in front of the Sun/Moon Deck, cutting the distance in right field from 366’ to 342’. This area was called the Goat Run or the Chicken Run or the Giles’ Chicken Run. This was expected to aid the popular, sleeveless strongman Ted Kluszewski. The right-field fence intersected at a point with the center field concrete wall. This necessitated a home run line, a white vertical stripe painted on the center field wall that read “Batted ball hitting concrete wall on fly to right of white line – home run.” Never before or since has a ground rule been painted on an outfield wall.

The Reds were pioneers in accommodating their opponents. In the 1930s they became the first team to install a clubhouse for the visiting team. And an added bonus for the fans: both teams’ clubhouses were located behind the left field stands. Players and coaches had to walk amongst the crowd to enter and leave the playing field. Of these fans, the most celebrated was Harry Thobe. Dancing a perpetual jig, flashing 12 gold teeth, the superfan and crowd entertainer attended almost every game in the 1940s and 1950s, wearing his customary white suit with red stripes, one red and one white shoe, a straw hat with a red band, and a red and white parasol.

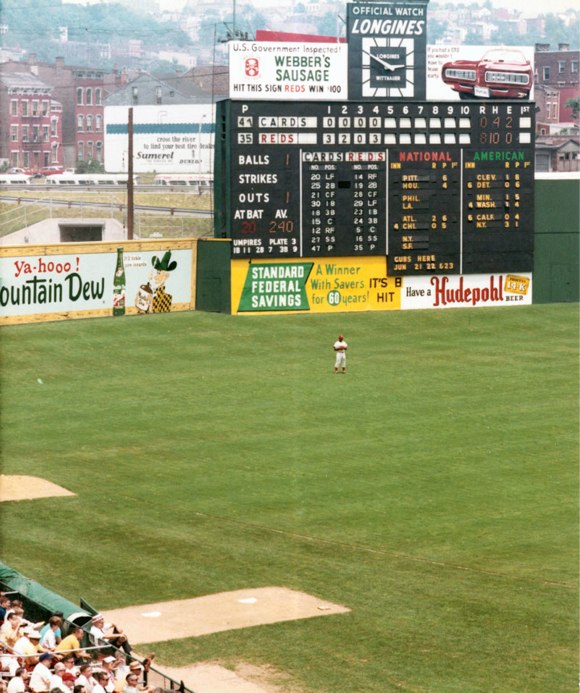

Major upgrades were undertaken at Crosley prior to the 1957 season. The red brick façade was painted white, new lights were installed and the largest scoreboard of its day replaced the old one in left center. The scoreboard stood 58 feet high and 65 feet wide. Atop the scoreboard was eight-foot-tall Longines clock. In addition to showing scores of all the major league games in progress and displaying full home and visiting team line-ups, the new board was the first to feature up-to-date players’ batting averages.

Perhaps the greatest moment in Crosley Field history came on May 24, 1935, when the Reds defeated Philadelphia 2-1 in the first night game in major league history. Twenty-six years earlier in 1909, inventor George Cahill had shown off a new portable lighting system. He built five steel towers for The Palace of the Fans and strung lights for an Elks Lodge game between Cincinnati and Newport, Kentucky. In 1931, the Reds shared portable lighting equipment with the touring House of David baseball team for a night exhibition. By the mid-thirties, with one in four Americans out of work and the rest employed from nine to five, Larry MacPhail was able to convince Powell Crosley and the minority partners to try night baseball. On that May night, with 20,422 onlookers in eager anticipation, FDR threw a switch 500 miles away in Washington and Crosley Field made history and baseball was changed forever.

Because of their standing as the first professional baseball team, traditionally the Reds were allowed to be the opening game of opening day. From 1876 to 1989, including the entire life of Crosley Field, the official beginning of each baseball season was in Cincinnati. The city would throw a parade and the Reds, in addition to hosting pre-game festivities, would bring in temporary seating in front of the left and right fences. The tradition of opening the season in Cincinnati ended recently with Major League Baseball acquiescing to ESPN and other nonsense, like opening the season in Tokyo in March. The parade does live on, however.

In 1929, the Reds became the first team to have daily radio coverage. In fact, a few years later, MacPhail gave the great Red Barber his first professional baseball radio gig. Crosley Field also held the first “Ladies Night” in 1936. “Ladies Night” took on a whole new meaning the year before.

Two months after MacPhail and the Reds turned on the lights for the first time, he had oversold the teams’ next night game by about 10,000 tickets. Fans from adjoining states — Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia — were pursued by the Reds to experience night baseball first hand. The marketing blitz proved successful and MacPhail had another sell out. When the game started, however, most of the out-of-towners had not arrived. Their trains had been delayed. The ticket staff went ahead and sold the late arriving tickets to an anxious walk-up crowd. When the trains finally arrived, fans were perplexed to see Crosley Field full and their seats taken. Seeing the potential for disaster, MacPhail went home and left his secretary in charge. Arguments erupted and fistfights ensued. Eventually thousands of fans were let on to the field, stationed behind ropes down the foul lines and in the outfield. In the bottom of the eighth, a local burlesque dancer named Kitty Burke rushed to home plate, grabbed Babe Herman’s bat and asked Reds hurler Paul Dean to pitch. After some trepidation, Dean obliged, throwing under handed, and getting the showgirl to ground out back to him. Later, Ms. Burke would bill her stage routine as “featuring the only girl who ever batted in the big leagues.”

Another notable Crosley Field moment was when the Mill Creek Flood of 1937 drowned the park in 21 feet of water. Reds pitcher Lee Grissom and traveling secretary John McDonald rowed a boat over center field.

Crosley Field was the site of four World Series (1919, ’39, ’40, and ’61) and two All-Star Games (1938 and 1953). The most (in)famous series of all was, of course, in 1919. The first two games were played at Crosley and won by the Reds. In Game One, Black Sox hurler Eddie Cicotte hit Reds leadoff batter Morrie Rath between the shoulder blades. This meant the fix was on and pools of money switched hands, all to be wagered on the Reds.

The Reds won back-to-back pennants in ’39 and ’40. The first year the Yankees swept the Reds, the final game featuring a tenth inning collision at the plate that knocked Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi out, allowing two more runs to score, putting the game out of reach at 7-4. The Reds got revenge the next year. With the brilliant pitching of Paul Derringer and Bucky Walters, they defeated the Tigers in seven games.

The first of Johnny Vander Meer’s back-to-back no-hitters was thrown at Crosley on June 11, 1938. Nine years later Ewell “the Whip” Blackwell almost duplicated the feat. On June 18, 1947, Blackwell no-hit Boston. Four days later, he went eight and one-third hitless innings until visiting Brooklyn second baseman Eddie Stanky broke up the bid in the ninth.

More history was made at Crosley on June 10th, 1944 when 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall took the mound and became the youngest player in major league history. His line on the day: 2/3 of an inning, five runs on five walks, two singles and a wild pitch. Final score: Cardinals 18, Reds 0.

More firsts: the first twin nine-inning no-hitter was thrown at Crosley when the Reds’ Fred Toney went toe-to-toe against the Cubs’ Hippo Vaughn. Crosley was also the first parked leased to the Negro Leagues (the Cuban Stars of the 1920s, the Cincinnati Tigers in 1937, and the Cincinnati Clowns in the 1940s).

The Reds monopolized the Most Valuable Player Award from 1938-1940 (Lombardi, Bucky Walters, Frank McCormick respectively) and the Redlegs of the 1950s (they weren’t called the Reds then because of communist hysteria; note the scoreboard above) marched out the most imposing group of sluggers in the league: Wally Post, Ted Kluszewski, Gus Bell, Ed Bailey, and a rookie who set a record with 38 dingers in 1956, Frank Robinson. Some of the cogs and wheels of the Big Red Machine, Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, Tony Perez, Davey Concepcion and Don Gullett, had their start at Crosley Field.

In 1970, in one of its last great moments, Crosley Field was the site of Hank Aaron’s 3,000 hit.

By the 1960s, the economic growth that Cincinnati was experiencing was all but absent from the warehouses and factories of the west end of town. When the Superior Towel and Linen Service laundry left the area and took with it one of Crosley’s hallmarks, it symbolically predicted the Reds’ abandonment of the area. The team, playing in the major’s smallest stadium, was eager to jump on the multi-purpose stadium bandwagon and flee to the publicly financed Riverfront Stadium downtown on the banks of the Ohio. The final game at Crosley was played on June 24, 1970. Over 28,000 nostalgic fans saw Johnny Bench and Lee May homer to edge Juan Marichal and the Giants, 5-4. After the game, a helicopter transported home plate to the new digs downtown. Crosley would spend the next two years as an auto impound lot and was eventually bulldozed in 1972. An industrial park now occupies the site.

Fifteen miles northeast of downtown lies the suburb of Blue Ash, where a life-size replica of Crosley Field stands as a memorial to the venerable park. Six hundred of the original seats were installed, the same ticket booths are used, and there the colossal scoreboard sits, displaying the batting orders, umpires, and line scores of Crosley’s last game, forever frozen in time. –Joe Schwei

DIMENSIONS

| Year | LF | LC | C | RC | RF |

| 1912 | 360 | 380 | 420 | 383 | 360 |

| 1921 | 320 | 380 | 420 | 383 | 384 |

| 1926 | 352 | 380 | 417 | 383 | 400 |

| 1927 | 339 | 380 | 395 | 383 | 383 |

| 1930 | 339 | 380 | 393 | 383 | 383 |

| 1931 | 339 | 380 | 407 | 383 | 383 |

| 1933 | 339 | 380 | 393 | 383 | 383 |

| 1936 | 339 | 380 | 407 | 383 | 366 |

| 1938 | 328 | 380 | 387 | 383 | 366 |

| 1939 | 328 | 380 | 380 | 383 | 366 |

| 1940 | 328 | 380 | 387 | 383 | 366 |

| 1942 | 328 | 380 | 387 | 383 | 342 |

| 1944 | 328 | 380 | 390 | 383 | 342 |

| 1950 | 328 | 380 | 390 | 383 | 366 |

| 1953 | 328 | 380 | 390 | 383 | 342 |

| 1955 | 328 | 380 | 387 | 383 | 342 |

| 1958 | 328 | 380 | 387 | 383 | 366 |

CAPACITY

| 1912 | 25,000 |

| 1927 | 30,000 |

| 1938 | 33,000 |

| 1948 | 30,000 |

| 1952 | 29,980 |

| 1958 | 29,603 |

| 1960 | 30,328 |

| 1961 | 30,274 |

| 1964 | 29,603 |

ATTENDANCE

| Year | Attendance | Average | Rank in League | Record | Standing |

| 1912 | 344,000 | 4,468 | 4th out of 8 | 70-83 | 4 |

| 1913 | 258,000 | 3,308 | 6th out of 8 | 64-89 | 7 |

| 1914 | 100,791 | 1,039 | 8th out of 8 | 60-94 | 8 |

| 1915 | 218,878 | 2,771 | 8th out of 8 | 71-83 | 7 |

| 1916 | 255,846 | 3,366 | 7th out of 8 | 60-93 | 8 |

| 1917 | 269,056 | 3,363 | 5th out of 8 | 78-76 | 4 |

| 1918 | 163,009 | 2,296 | 4th out of 8 | 68-60 | 3 |

| 1919 | 532,501 | 7,607 | 2nd out of 8 | 96-44 | 1/WS |

| 1920 | 568,107 | 7,378 | 3rd out of 8 | 82-71 | 3 |

| 1921 | 311,227 | 4,095 | 7th out of 8 | 70-83 | 6 |

| 1922 | 493,754 | 6,250 | 6th out of 8 | 86-68 | 2 |

| 1923 | 575,064 | 7,373 | 4th out of 8 | 91-63 | 2 |

| 1924 | 473,707 | 6,233 | 5th out of 8 | 83-70 | 4 |

| 1925 | 464,920 | 6,117 | 5rd out of 8 | 80-73 | 3 |

| 1926 | 672,987 | 8,749 | 4th out of 8 | 87-67 | 2 |

| 1927 | 442,164 | 5,527 | 6th out of 8 | 75-78 | 5 |

| 1928 | 490,490 | 6,288 | 6th out of 8 | 78-74 | 5 |

| 1929 | 295,040 | 3,783 | 7th out of 8 | 66-88 | 7 |

| 1930 | 386,727 | 5,022 | 6th out of 8 | 59-95 | 7 |

| 1931 | 263,316 | 3,420 | 7th out of 8 | 58-96 | 8 |

| 1932 | 256,950 | 4,636 | 5th out of 8 | 60-94 | 8 |

| 1933 | 218,281 | 2,763 | 7th out of 8 | 58-94 | 8 |

| 1934 | 206,773 | 2,651 | 7th out of 8 | 52-99 | 8 |

| 1935 | 448,247 | 5,898 | 5th out of 8 | 68-85 | 6 |

| 1936 | 466,345 | 6,136 | 4th out of 8 | 74-80 | 5 |

| 1937 | 411,221 | 5,140 | 6th out of 8 | 56-98 | 8 |

| 1938 | 706,756 | 9,179 | 3rd out of 8 | 82-68 | 4 |

| 1939 | 981,443 | 12,117 | 2nd out of 8 | 97-57 | 1 |

| 1940 | 850,180 | 11,041 | 2nd out of 8 | 100-53 | 1/WS |

| 1941 | 642,513 | 8,146 | 3rd out of 8 | 88-66 | 3 |

| 1942 | 427,031 | 5,546 | 6th out of 8 | 76-76 | 4 |

| 1943 | 379,122 | 4,861 | 7th out of 8 | 87-67 | 2 |

| 1944 | 409,567 | 5,251 | 6th out of 8 | 89-65 | 3 |

| 1945 | 290,070 | 3,767 | 7th out of 8 | 61-93 | 7 |

| 1946 | 715,751 | 9,295 | 8th out of 8 | 67-87 | 6 |

| 1947 | 899,975 | 11,688 | 8th out of 8 | 73-81 | 5 |

| 1948 | 823,386 | 10,693 | 7th out of 8 | 64-89 | 7 |

| 1949 | 707,782 | 9,074 | 8th out of 8 | 62-92 | 7 |

| 1950 | 538,794 | 7,089 | 8th out of 8 | 66-87 | 6 |

| 1951 | 588,794 | 7,640 | 7th out of 8 | 68-86 | 6 |

| 1952 | 604,197 | 7,847 | 7th out of 8 | 69-85 | 6 |

| 1953 | 548,086 | 7,027 | 8th out of 8 | 68-86 | 6 |

| 1954 | 704,167 | 9,145 | 7th out of 8 | 74-80 | 5 |

| 1955 | 693,662 | 9,009 | 7th out of 8 | 75-79 | 5 |

| 1956 | 1,125,928 | 14,622 | 3rd out of 8 | 91-63 | 3 |

| 1957 | 1,070,850 | 13,907 | 4th out of 8 | 80-74 | 4 |

| 1958 | 788,582 | 10,241 | 8th out of 8 | 76-78 | 4 |

| 1959 | 801,298 | 10,406 | 7th out of 8 | 74-80 | 5 |

| 1960 | 663,486 | 8,617 | 8th out of 8 | 67-87 | 6 |

| 1961 | 1,117,603 | 14,514 | 4th out of 8 | 93-61 | 1 |

| 1962 | 982,095 | 12,125 | 4th out of 10 | 98-64 | 3 |

| 1963 | 858,805 | 10,603 | 7th out of 10 | 86-76 | 5 |

| 1964 | 862,466 | 10,518 | 7th out of 10 | 92-70 | 3 |

| 1965 | 1,047,824 | 12,936 | 7th out of 10 | 89-73 | 4 |

| 1966 | 742,958 | 9,405 | 9th out of 10 | 76-84 | 7 |

| 1967 | 958,300 | 11.831 | 7th out of 10 | 87-75 | 4 |

| 1968 | 733,354 | 8,943 | 8th out of 10 | 83-79 | 4 |

| 1969 | 987,991 | 12,197 | 8th out of 10 | 89-73 | 3 |

Trivia

- First MLB home run hit in Crosley Field: Jimmy Esmond, Cincinnati Reds, 4/21/1912.

- Player who hit the most home runs hit in Crosley Field: Frank Robinson, 174 (all as a Red), and Eddie Matthews (59 as a visiting player).

- Total home runs hit in Crosley Field: 4,558

- Johnny Vander Meer is the only man to throw consecutive no-hitters. The first one was thrown at Crosley Field on June 11, 1938; he followed it up with a June 15 no-hitter of the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field.

- The neighborhood surrounding the Crosley Field site also hosted early professional baseball teams. The 1869 Red Stockings played two blocks away at Union Grounds (the site is now part of the Cincinnati Museum Center), while the 1882 Red Stockings played at Bank Street Grounds, located tow blocks away as well. Plus, the Reds’ home before Crosley Field — the Palace of the Fans — was in the same location.

- It was not until 1938 that a press box was added to Crosley Field.

- In 1947 pay phones were removed from the ballpark to cut down on the amount of illegal gambling on Reds games.

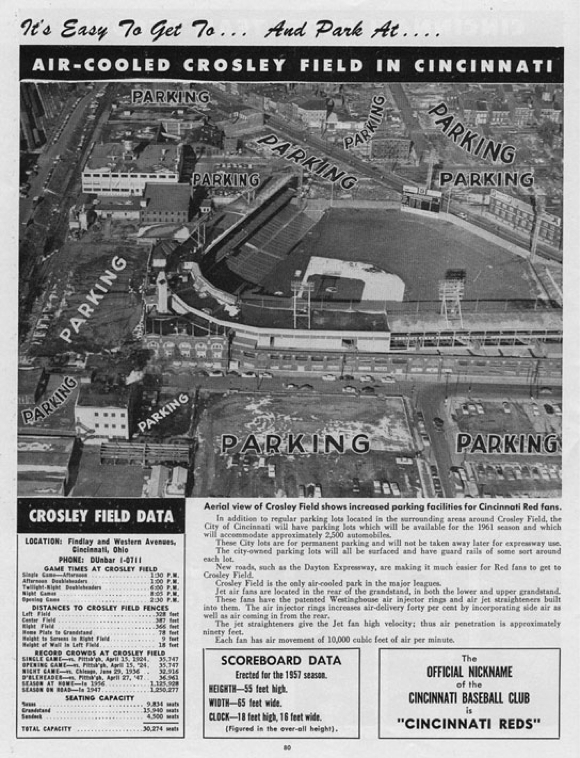

- By 1961 the Reds advertised Crosley Field as being “air-cooled,” as Westinghouse fans were used at the ends of the grandstand to circulate air throughout.

—-

Share your news with the baseball community. Send it to us ateditors@augustpublications.com.

Are you a subscriber to the weekly Ballpark Digest newsletter? You can sign up for a free subscription at the Newsletter Signup Page.

Join Ballpark Digest on Facebook and on Twitter!

Follow Ballpark Digest on Google + and add us to your circles!