Lost in all the excitement about plans for a new Howard Terminal ballpark unveiled by the Oakland Athletics and Bjarke Ingels Group last week is a radical proposal to make over the current Oakland Coliseum site. The big question: Is the Coliseum worth saving?

The A’s ownership pitched the Coliseum site makeover as an economic-development tool both for the team and for the city: the Howard Terminal ballpark itself is unlikely to generate enough revenue to cover debt service, so the team will use revenues from the Coliseum redevelopment to cover shortfalls. The team is planning to upgrade the current Coliseum complex into a mixed-use development, complete with retail and office space, a youth-sports facility and an event space with a new amphitheater. The Coliseum would be torn down, but Oracle Arena would remain open for concerts, events and perhaps a sports exhibition or two. The overall goal is to keep the site alive with plenty of destination events, and the current pluses of the location—freeway and BART access—would continue to be important in programming.

Of course, this comes with a few caveats. First, the Coliseum site needs to be acquired from both Oakland and Alameda County at a reasonable price, which probably will not be the result of any public bidding. Second, the A’s will need to tackle both development of a new ballpark and related offerings (office space, retail, etc.) as well as the overhaul of the Coliseum site. While much of the work will be staggered—the Howard Terminal work would come well before the Coliseum is torn down—those are still huge tasks for any MLB team.

So while the plan has the initial approval of city leaders who see it killing two birds with one stone, a large question looms: Should the Coliseum be torn down?

A Little Coliseum History

In the proposed redevelopment plan, the Coliseum would be torn down to make way for the amphitheater and tech campus with a diamond set to commemorate the A’s (and, we presume, the Raiders).

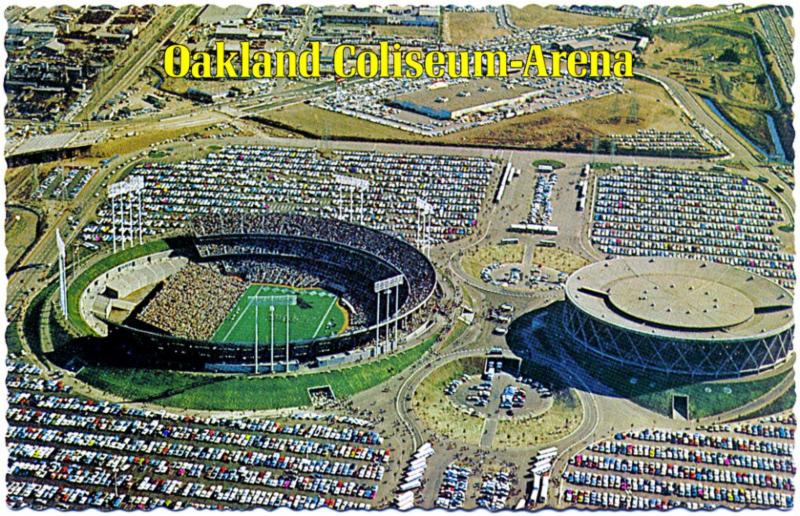

The Coliseum predates the A’s move to Oakland, opening in September 1966. The first event was an AFL match between the Kansas City Chiefs and Oakland Raiders, who had bounced around the Bay Area since the league’s formation, including a stint playing at Candlestick Park. The Oakland Seals, then of the WHL, played at what was then known as the Oakland-Alameda County Stadium Arena in 1966-1967 before joining the NHL as part of the landmark 1967 expansion as the California Seals.

Expansion fever was present in all four major American sports in the 1960s, and a number of venues were constructed to take advantage of rising interest and expanding television revenue. One such model was a dual-facility approach, including both an arena and a baseball/football venue. We saw that model used in Minneapolis-St. Paul (Met Center and Met Stadium) and Philadelphia (Veterans Stadium and the Spectrum), and the original site plan for Kansas City’s Truman Sports Complex included an arena in addition to the football and baseball facilities.

When the Oakland Coliseum was designed, it was part of the cookie-cutter trend in sports facilities, which features a circular design and moveable seating to accommodate both baseball and football. That model was pioneered by RFK Stadium, which opened in fall 1961 as home to the NFL’s Redskins and MLB’s Washington Senators.

The design from George A. Dahl and Osborn Engineering took a quantum leap forward in treating baseball and football equally. This greatly benefited pro football, where teams had played as lesser tenants in MLB ballparks and college stadiums. In a move copied by designers of other cookie-cutter stadiums in New York City, St. Louis, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Oakland, San Diego, Cincinnati, Philadelphia and Atlanta, a circular design allowed for the movement of seating areas depending on the event. In the case of RFK Stadium, the left-field bleachers were moved on tracks, and those bleachers became the equivalent of a stadium bouncy house. Get enough fans jumping around, and the whole stadium shook.

While cookie-cutter stadiums from the 1960s and 1970s were derided by fans as failing to provide decent football or baseball experiences, that wasn’t true at RFK Stadium. Maybe it’s because the stadium bowl wasn’t a true circle, that the curvy roofline provided some visual interest, or maybe what was cutting edge in 1961 became charmingly retro by 2005. Yes, it wasn’t a great ballpark in 2005 when the Washington Nationals debuted, but it was still a fun place to see a ballgame, particularly from one of the Frank Howard seats painted white to show where one of his bombs landed.

The Coliseum Today

The experience at the Oakland Coliseum today isn’t nearly so charming. The circular design is a hindrance to good sightlines, and it has a definite effect on the playing conditions with huge stretches of foul area. Mount Davis in center field, constructed for the return of the Oakland Raiders, is an eyesore when it comes to baseball and cuts off what was once one of the most charming backdrops in baseball. That circular design that looks so nice in overhead shots leads of a slew of bad seats in real life, and there’s no way an adaptive reuse plan can address the basic architecture of the place.

The idea of the closed concourse featured in the Coliseum goes against what’s considered good facility design these days: head for a beer or a brat and you’ll miss plenty of action. There are also no good spots to just hang out and watch the action: social spaces are all the rage in sports venues, and while the A’s have worked to create some at the Coliseum, there are limitations present.

And the place is falling apart, with well-documented drainage and sewage issues in recent years. Lord know what else needs fixing: anyone who’s owned an old home knows that sense of dread when it comes to renovations, because you never know what you’ll find when you begin opening walls. It’s the fifth-oldest ballpark left in Major League Baseball, behind Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, Dodger Stadium and Angel Stadium.

The Swingin’ A’s and the Bash Brothers

There is an emotional argument for keeping the Coliseum in some form: nostalgia. The A’s won four World Series (1972-1974, 1989) while playing out of the Coliseum, and the Raiders won two Super Bowls during their first stint in Oakland. Charlie Finley took sports marketing to another level with the handlebar moustaches and Swingin’ A’s in the 1970s, and Bash Brothers brought a revival of baseball in Oakland.

But is nostalgia enough to preserve a facility with no viable streams of revenue once a new ballpark gets built? There are some in the Bay Area arguing either to renovate the Coliseum or build a new ballpark next to the Coliseum a la Shea Stadium/Citi Field or Cinergy Field/Great American Ball Park. The A’s proposed that once, but it went nowhere.

It’s pretty clear the A’s don’t see a continuing use for the Coliseum, and neither do new football startups Alliance of American Football (AAF) or XFL; both leagues completely bypassed the Bay Area when mapping out inaugural seasons. And while there was a proposal for a new USL stadium at the Coliseum site (which apparently won’t happen), the facility isn’t seen as being a viable soccer home, either. Without the NFL or MLB, it’s pretty clear the Coliseum is economically obsolete, especially with AT&T Park and Levi’s Stadium competing for big-ticket events requiring the capacity of a Coliseum. And while the new Howard Terminal ballpark and Coliseum site renovation plans are still in the beginning phases, it’s clear that the Oakland Coliseum is facing its final days hosting MLB baseball.

This article first appeared in the Ballpark Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? It’s free, and you’ll see features like this before they appear on the Web. Go here to subscribe to the Ballpark Digest newsletter.